On Implementation.

Before moving on to today’s subject, an acknowledgment that this marks the first Dean’s Note since entering a new and uncertain political era. Donald Trump’s inauguration as President of the United States is a milestone in our country’s history, and will likely have profound implications for public health. Respecting the strong feelings that this event has evoked, both positive and negative, I will take the next two notes to comment on how we might use this moment to further the goals of public health through a focus on promoting justice. Before tackling this theme, however, a note, perhaps fittingly, on implementation, and the complex work of mobilizing our aspirations in a changing, sometimes chaotic world.

Before moving on to today’s subject, an acknowledgment that this marks the first Dean’s Note since entering a new and uncertain political era. Donald Trump’s inauguration as President of the United States is a milestone in our country’s history, and will likely have profound implications for public health. Respecting the strong feelings that this event has evoked, both positive and negative, I will take the next two notes to comment on how we might use this moment to further the goals of public health through a focus on promoting justice. Before tackling this theme, however, a note, perhaps fittingly, on implementation, and the complex work of mobilizing our aspirations in a changing, sometimes chaotic world.

如果

We can perhaps ground our thinking in the formal work of implementation science, a growing field. Implementation science has been defined as the “scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of clinical research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice,” in order to better link discovery with delivery of evidence-based interventions.

Applying this to health, we inevitably start with the delivery of medical care services, where much of the literature is grounded. Bollinger and Kruk recently conducted a review of innovations aimed at expanding access and improving quality of maternal and child health care services in low- and middle-income countries. They found that there was little overall guidance in the literature as to which interventions truly produced results, due in part to the lack of coherent methodological frameworks needed to direct the evaluation of interventions that seem promising but need further testing. This problem is not, however, unique to medical care, and it is not new. Going back 30 years, a 1985 article published in Harvard Business Review describes some of the challenges of implementing new technology in general, including resistance to change and the difficulty of promotion.

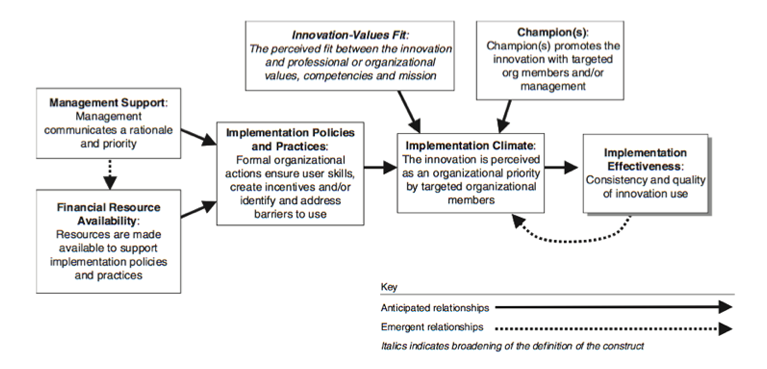

Jacobs and colleagues evaluated an innovation implementation framework that was originally developed for manufacturing, but has recently been applied to health care in the context of the National Cancer Institute’s Community Clinical Oncology Program (Figure 1). Their quantitative analyses confirmed the relationships highlighted in the framework, including the importance of the organizational climate for successful implementation of innovation in medical care.

Helfrich CD, Weiner BJ, McKinney MM, Minasian L. Determinants of implementation effectiveness . Medical Care Research and Review. 2007; 64(3): 279—303.

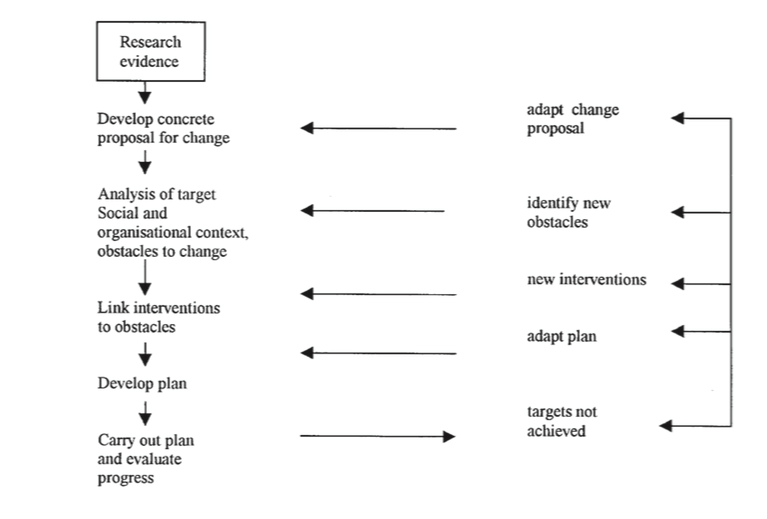

Other frameworks for interventions have also been proposed, such as the earlier, slightly more linear one from Grol and Jones (Figure 2). The implementation science field has since evolved; recently, researchers have called for more complex approaches to implementation. This was particularly necessary in the Millennium Development Goals era, when it became clear that although more funding was available to try to meet these goals by reducing maternal and child mortality, as well as HIV, throughout the world, many new programs were not properly evaluated, making it difficult to know which interventions actually worked. In this context, Victoria and colleagues called for more analytic techniques, multi-level indicators, and transparency for large-scale programs.

Grol R, Jones R. Twenty years of implementation research. Family Practice. 2000; 17: S32—S35.

What do I take from these frameworks? It seems to me that there are four principal components to successful implementation: political support, adequate funding, clear communication, and the effective management of logistics. There is also the matter of context, which is considered crucial to many of the frameworks that are applied to implementation science.

我们

I think these dimensions indeed represent what matters to implementation success. At core, though, there remains the role of context, without which I am not sure that any innovation can ever be implemented. The fight against polio and the push for safer roads are public health success stories not just because they represent a successful confluence of logistics, communication, funding, and political will leading to effective implementation. They are successes because they have managed to influence culture, nudging it in the direction of healthier populations. Childhood vaccination, regular seatbelt use—these have become expected behaviors in our daily lives, touching on something more fundamental than the rollout of a single program or even a national campaign. Rather, they help to create a society that is hardwired for greater well-being and more receptive to the work of public health.

Globally, we have seen how engaging with culture and social norms—foundational determinants of health—aids implementation. In Zimbabwe, for example, there has been a 34 percent decline in new HIV infections between 2005 and 2013, due, in large part, to cultural change around the issue of HIV, as well as the implementation of measures like condom distribution and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission with Option B+. In Cameroon, progress has been made against malaria through the distribution of more than 8 million long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets; this progress has been driven by a media campaign that has helped to foster a “net use culture.”

佛

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A Knox Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo, Laura Sampson, and Professor Mari-Lynn Drainoni for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: /sph/tag/deans-note/