Learning from Sweden.

Before I begin today’s note, an acknowledgement of International Women’s Day 2017, which will take place Wednesday, March 8. I have written before about gender equity as a core concern of public health, and we are today rerunning the Dean’s Note on that. I would like to note the optimism that comes, even in trying comes, with the movements that are emerging, from the Women’s March to the “Day Without a Woman” strike planned for this Wednesday, suggesting that there remain many reasons to hope that we are still moving forward—at times haltingly, but forward nonetheless—toward a more equitable world.

Before I begin today’s note, an acknowledgement of International Women’s Day 2017, which will take place Wednesday, March 8. I have written before about gender equity as a core concern of public health, and we are today rerunning the Dean’s Note on that. I would like to note the optimism that comes, even in trying comes, with the movements that are emerging, from the Women’s March to the “Day Without a Woman” strike planned for this Wednesday, suggesting that there remain many reasons to hope that we are still moving forward—at times haltingly, but forward nonetheless—toward a more equitable world.

On to today’s note. During the rancorous political primary season of 2016, Bernie Sanders, then a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, said, “I think we should look to countries like Denmark, like Sweden, and Norway, and learn from what they have accomplished.” Perhaps predictably, he faced withering media criticism for his comment, and his primary opponent—eventual Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton—largely rejected the idea that we should focus too much on the underlying social and political structures that have shaped Scandinavian countries. Last month, the subject of Sweden was raised again, this time by President Trump, who, in a vague statement at a rally, appeared to suggest that the country had recently experienced a terror attack as a result of its refugee policies, despite no such incident having taken place.

Amidst these contretemps, the fact remains that from many perspectives—not the least of which is that of population health—there is much to envy about what Sweden has achieved, and perhaps something to learn that can be applied to other countries, including, but not limited to, the United States. A note, then, about Sweden, focusing on its approach to population health.

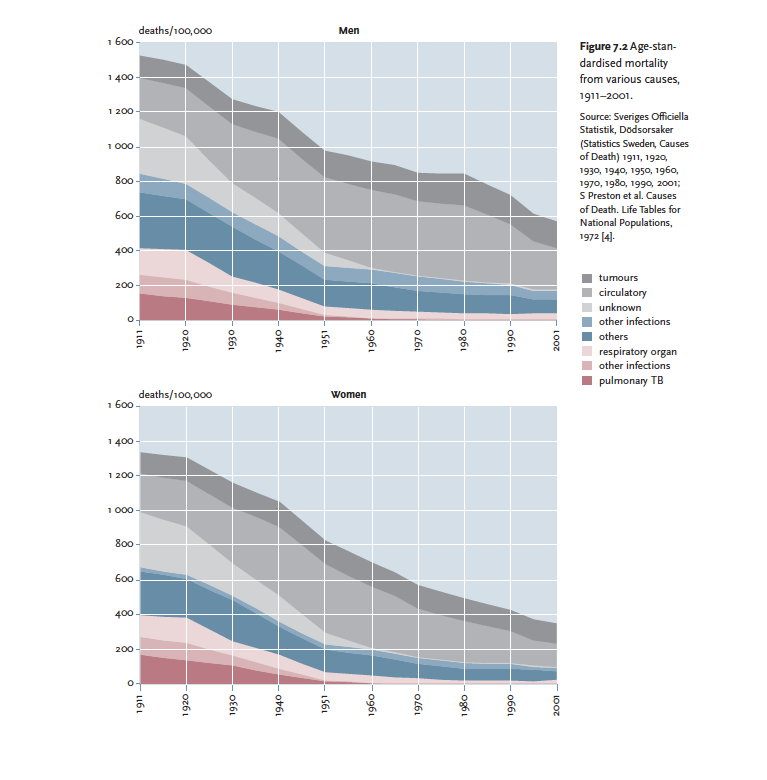

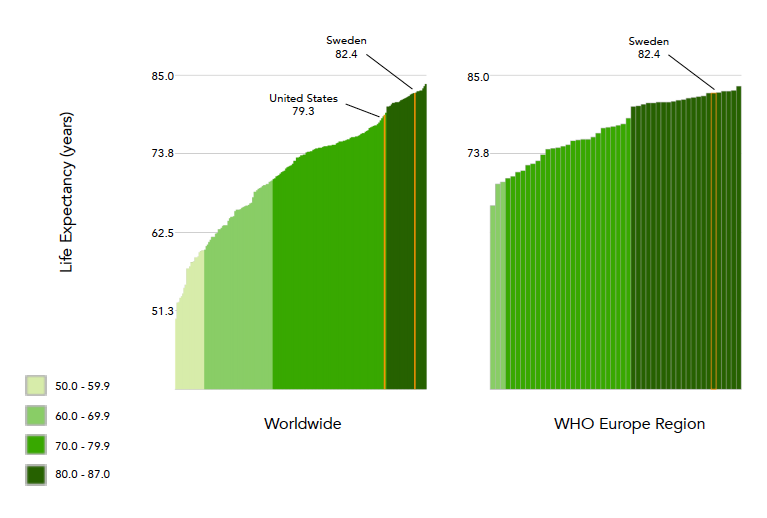

Age-standardized mortality has declined significantly over the 20th century (Figure 1), and Sweden currently has one of the highest life expectancies in the world, at 82.4 years (Figure 2), an indicator that increased by 3.6 years between 1990 and 2015.

From: Sundin J, Willner S. Social change and health in Sweden: 250 years of politics and practice. Solna, Sweden: Swedish National Institute of Public Health; 2007. Accessible at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:17729/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Graphs generated using the WHO Global Health Observatory website: http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends/en/

Sweden also has one of the lowest infant mortality rates (Figure 3) in the world and in their WHO global region, not least because of their exemplary midwifery program.

Graph generated using the WHO data visualizations dashboard website: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.sdg

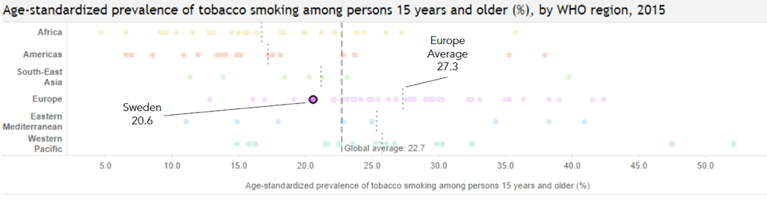

While the prevalence of tobacco smoking in Sweden is only slightly lower than the global average (Figure 4), it is well below the European regional average, and has decreased substantially over the last 30 years.

Graph generated using the WHO data visualizations dashboard website: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.sdg

What accounts for Sweden’s encouraging health indicators? At core, the past century has seen the reformulation of the Swedish public health system through a dedicated focus on the promotion of social welfare policies that engender population health. This focus is entirely consistent with the notion that to promote the health of populations we need to invest in the social, cultural, and political factors that promote health.

The genesis of Sweden’s efforts, which spanned the past century, emerged from a history of regional and sociodemographic health inequalities that gave way to legislative efforts designed to encode health equity into the operation of the national public health system. Even as child mortality declined dramatically around the turn of the century, a socioeconomic gradient in child mortality sharpened, motivating the improvement of health equity. Beginning in the early 20th century, Sweden saw the establishment of aid for the poor and a rise in the protections of workers through the establishment of unemployment, health insurance, and pension plans as core priorities. As the welfare state and protections for occupational health expanded, the Swedish Public Health Institute was established, with the charge of “preserving or improving public health.” This institute was eventually supplanted by the Swedish National Institute of Public Health in 1992, and the Public Health Agency of Sweden.

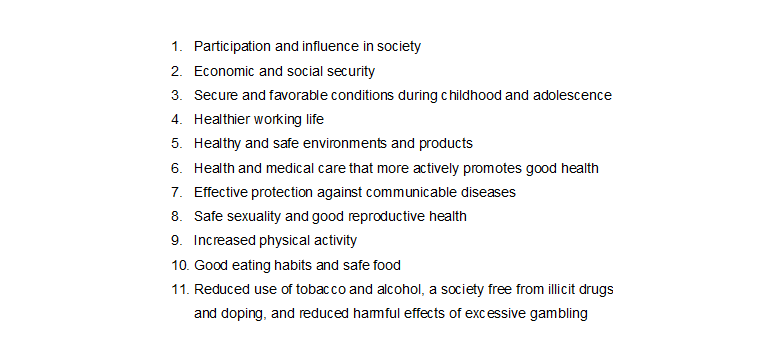

A series of core legislative efforts cemented Sweden’s embrace of progress in the service of health. Over 30 years ago, Sweden passed the Health and Medical Services Act of 1982, guaranteeing access to health services according to need for all Swedish residents. Critically, in 2003, Sweden passed the Comprehensive Swedish Public Health Policy (CSPHP) seeking “to create the social conditions to ensure good health on equal terms for the entire population.” As seen in Box 1, the CSPHP organized the work necessary to achieve this mission into 11 domains. These domains inform how Sweden approaches its legislative efforts, serving as a sort of “strategy map” for the country.

From: Hogstedt C, Lundgren B, Moberg H, Pettersson B, Ågren G. Background to the new Swedish public health policy. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2004; 32(Supplement 64): 6—17.

An illuminating example: Toward the end of domain one (participation and influence in society), Sweden implemented over the period of 2012 to 2016 the Madrid International Plan of Aging, which was aimed at strengthening the rights of older adults. Financial incentives were offered to employers to hire older workers, and opportunities for government-funded rehabilitation services were further extended to the elderly. Additionally, support for independent living has been promoted through investment in home modification and the broadening of support services. Finally, this work has included the strengthening of anti-discrimination laws aimed at ensuring the equal treatment of the elderly throughout society.

In 2016, Sweden extended the parental leave benefit from two to three months, furthering the ends of gender equity and domains three (secure and favorable conditions during childhood and adolescence), and four (healthier working life). In addition to improving the quality of working life for all, this will promote a more gender-equal work and parenting environment, which should, in turn, result in healthier conditions for children.

Bolstering a strong set of alcohol taxation and regulatory policies, the Swedish public health system has approached domain 11 (reduced use of tobacco and alcohol, a society free from illicit drugs and doping, and reduced harmful effects of excessive gambling) by organizing broad working groups aimed at reducing drunkenness and violence in places that serve alcohol. This Responsible Beverage Service program focuses on the training of service staff to avoid serving alcohol to visibly intoxicated individuals and to be able to identify situations of potential conflict. Although Sweden still struggles with increasing per capita consumption of alcohol, there is some evidence of a decrease in alcohol-related problems in much of the country. Further, the efforts of the Responsible Beverage Service program have been successful in reducing assaults.

In addition to the above non-traditional public health strategies, Sweden has been a strong proponent of the health in all policies approach. Accordingly, Sweden has used health impact assessments to ensure a cross-sectoral approach to decisions that are not commonly thought of in public health terms. For example, a health impact assessment was performed for the remodeling of Route 73, a major road connecting Stockholm to one of the smaller local municipalities. The route was due for a remodeling to reduce the incidence of traffic accidents. The assessment examined the determinants of health in the traffic environment (i.e. risk of accident), living environment (i.e. exposure to pollution), and recreational environment (i.e. outdoor recreational activities), while also considering the equality of health outcomes. The CSPHP and the equity focus of Swedish policy have provided support for the adoption and use of health impact assessments.

My read of the Swedish approach is that it has been successful in furthering the health of the public and the broader mission of health equity, serving as an example both to other European countries and to the wider world. It is worth noting, of course, that Sweden is not nirvana; no country ever is. There are several areas where Sweden falls short on health. For example, immigrants to Sweden carry a greater burden of trauma than the rest of the population, have higher risks of suicide, and face challenges to societal integration, in addition to discrimination. Additionally, while the public health system is squarely focused on equity, it is clear that regional and educational differences persist. For example, while the life expectancy in Sweden increased by 3.6 years between 1990 and 2015, increases were greater than the country level average in Stockholm (five years), and lower in the rest of the country (3.3 years).

And yet, in my assessment, these limitations pale in light of the overall success that the country has had in maintaining an excellent overall health profile supported by an exemplary set of guiding public health frameworks that regard social welfare as inextricable from the core mission of public health. Importantly, it was not always thus; the Swedish example illustrates that the production of population health is a result of deliberate actions on the part of the state that aim to improve social, economic, and political conditions to the end of improving population health. Our national conversation about what we can learn from Scandinavia is, unfortunately, much more about sloganeering than it is about ideas. Rather, we must engage with the complex conversations that we need to have about how we value health and how we can best advance the health of populations. It seems that such a national conversation would indeed serve us well.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the contributions of Greg Cohen, MSW, and Joana Lima to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: /sph/tag/deans-note/