Tradeoffs in Disease Screening.

I start today’s Dean’s Note noting, once again, that another gun-related tragedy, this time in San Bernardino, has claimed 14 lives, injuring 21 others. The event is made ever so more poignant by its hitting of public health professionals. This issue persists, remaining a preventable public health epidemic, a tragedy that we allow to happen. I have written Dean’s Notes on this, including last week’s Dean’s Note. I also wanted to note that in many ways this falls squarely in the rubric of the argument I made in another Dean’s Note where we continue to find gun-related morbidity and mortality acceptable, when it should be thoroughly unacceptable. What sadness to reflect on more lives lost when we can do so much better. It is perhaps a ray of hope amidst the darkness to read a front-page editorial in the New York Times saying, “It is a moral outrage and a national disgrace that civilians can legally purchase weapons designed specifically to kill people with brutal speed and efficiency. ” I could not agree more. Could this be a piece of the moral outrage that we collectively need to create social momentum to bring about change?

I start today’s Dean’s Note noting, once again, that another gun-related tragedy, this time in San Bernardino, has claimed 14 lives, injuring 21 others. The event is made ever so more poignant by its hitting of public health professionals. This issue persists, remaining a preventable public health epidemic, a tragedy that we allow to happen. I have written Dean’s Notes on this, including last week’s Dean’s Note. I also wanted to note that in many ways this falls squarely in the rubric of the argument I made in another Dean’s Note where we continue to find gun-related morbidity and mortality acceptable, when it should be thoroughly unacceptable. What sadness to reflect on more lives lost when we can do so much better. It is perhaps a ray of hope amidst the darkness to read a front-page editorial in the New York Times saying, “It is a moral outrage and a national disgrace that civilians can legally purchase weapons designed specifically to kill people with brutal speed and efficiency. ” I could not agree more. Could this be a piece of the moral outrage that we collectively need to create social momentum to bring about change?

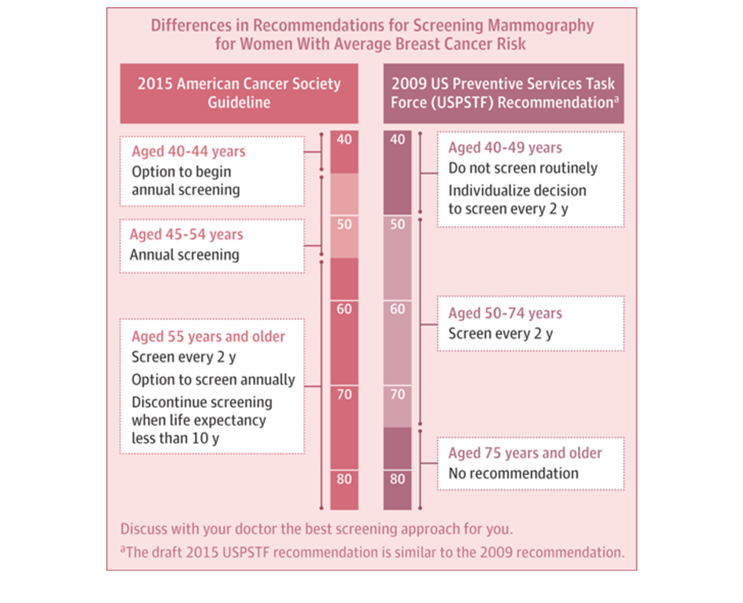

On to today’s note. Screening has been very much in the news lately, with the American Cancer Society (ACS) recently issuing new guidelines for breast cancer screening. Figure 1 below shows some of the new recommended mammography screening guidelines and how they compare with the latest set of guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force. Clearly there are some real differences between the new and older guidelines. These changes reflect both new data and emerging directions in the field.

Differences in recommendations for screening mammography, 2009 vs. 2015. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2463258

Why, though, is it so difficult for us to determine what screening is worthwhile, and what the optimal guidelines are to optimize health in populations? I take the occasion of the new ACS guidelines to revisit our understanding of screening—a core concept in population health.

The Fundamental Challenge: Early Disease Detection, and Disease Progression

Public health aims to prevent disease and promote health. To that end, screening, with its promise of detecting early markers of pathology and preventing disease, stands to be a core part of the public health armamentarium. However, this rests on the core concept that underlies screening: that we can detect pathology early in such a way that we can alter the progression of disease. And this is where, particularly in the case of some pathologies where our understanding continues to evolve, it becomes less than perfectly clear whether we should be screening or not.

Th

The emerging evidence suggesting we should be considering DCIS differently is mirrored by emerging evidence about the benefits of mammography itself.

A large-scale US study found that in the more than three decades since the introduction of breast cancer screening mammography, the rate of early stage detection doubled (112 to 234 cases per 100,000), while the rate of late stage identification decreased by only 8 percent (102 to 94 cases per 100,000). The authors suggest that in 2008, overdiagnosis accounted for 70,000 cases, or 31 percent of all breast cancers diagnosed; in the past 39 years, they estimate that 1.3 million US women have been overdiagnosed. An independent UK review on breast cancer published around the same time came to similar conclusions, estimating that for every case of breast cancer prevented, three cases are overdiagnosed. These data clearly suggest that our use of screening to detect disease early enough to make a difference is limited, and perhaps resulting in more, rather than less harm. Why is this?

Screening, Cutoffs, and the Heart of the Tradeoff

Sc

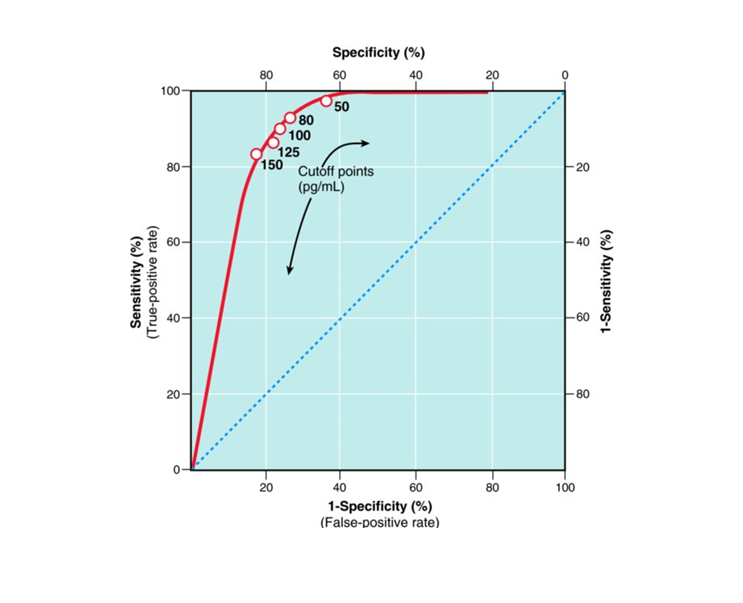

A receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve. The accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure with various cutoff levels of BNP between dyspnea due to congestive heart failure and other causes; Source: Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials (2012). Fletcher, R. H., Fletcher, S. W., & Fletcher, G. S.

Why Context Matters: How Population Prevalence Determines the Utility of a Test

阿宝

First Do No Harm: The Unintended Consequences of Unnecessary Screening

所以

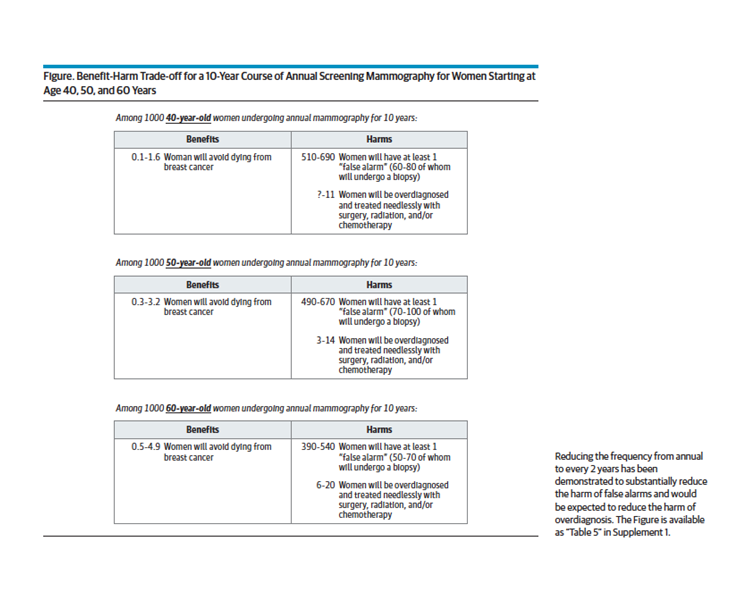

Welch and Passow offer a useful and instructive example about the consequences of unnecessary screening, shown in Figure 3 below.

Welch, H. G., & Passow, H. J. (2014). Quantifying the benefits and harms of screening mammography. JAMA internal medicine, 174(3), 448-454.

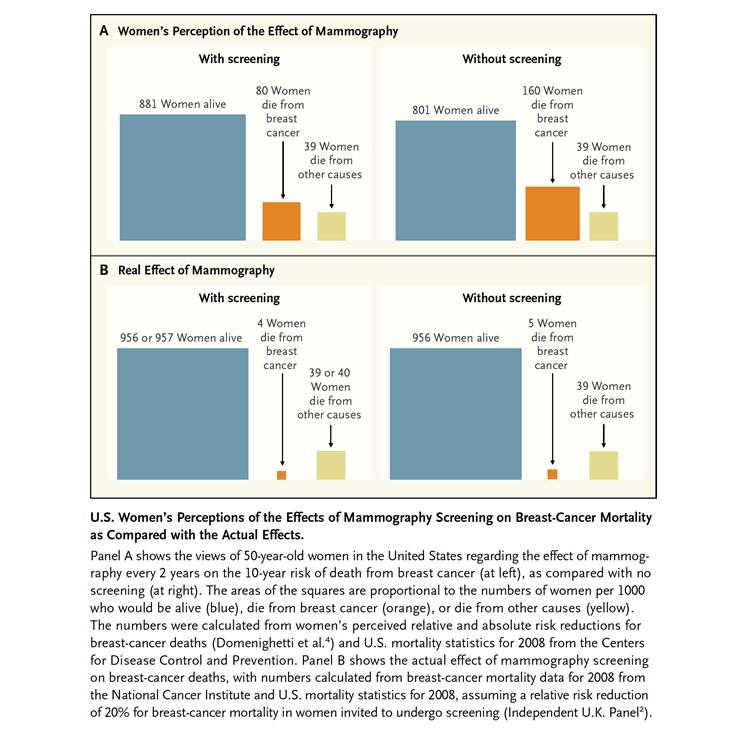

None of this is particularly easy. Screening appears to be a compelling social good. The endorsement of screening by celebrities has led to phenomena such as the Couric effect, where the endorsement of colonoscopy by a celebrity resulted in a temporary rise in the rates of colonoscopy in the population. In addition, general understanding of the benefits of screening often vary dramatically from the reality, as shown effectively in Figure 4.

Biller-Andorno N1, Jüni P. Abolishing mammography screening programs? A view from the Swiss Medical Board. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(21):1965-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1401875

In some ways it is easy to argue that “everyone should get screened” for any number of diseases, and we hear this argument not infrequently, including in regards to both breast cancer and prostate cancer. Unfortunately, the limitations of our screening tests for these diseases means that our screening is accompanied by both false positives and false negatives, and that we should weigh the benefits and harms of both before recommending screening for particular populations.

In general, I thought the new ACS guidelines commendable. They represent a judicious effort to grapple with a tough issue and to adopt the best evidence-informed guidelines for when and whom to screen, even accepting that we simply do not know enough about whether to screen or not at some ages. That strikes me as a suitable humble approach to data, and an effort to wrap our brain around complexity in order to recommend optimal screening to the end of preventing as much disease as possible, without doing harm, in populations.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the contributions of Gregory Cohen, MSW, to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: /sph/category/news/deans-notes/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.