Complexity and Population Health.

Before I begin today’s note, a quick follow-up to Tuesday’s School Assembly. For those of you not able to attend, I spoke briefly about the value of Twitter as both an internal and external communications tool—a space in which we not only can broadcast our research and institutional accomplishments, but can also connect with our public health peers, current and prospective students, alumni, international constituents, and health care journalists. Serendipitously, Jeffrey Flier, the dean of Harvard Medical School, wrote a column that same day explaining why he joined Twitter and the rewards of entering the space. It is worth a quick read; those then looking for a tutorial on how to join Twitter can contact Meaghan Agnew, who oversees our social media, at meaghans@bu.edu.

Before I begin today’s note, a quick follow-up to Tuesday’s School Assembly. For those of you not able to attend, I spoke briefly about the value of Twitter as both an internal and external communications tool—a space in which we not only can broadcast our research and institutional accomplishments, but can also connect with our public health peers, current and prospective students, alumni, international constituents, and health care journalists. Serendipitously, Jeffrey Flier, the dean of Harvard Medical School, wrote a column that same day explaining why he joined Twitter and the rewards of entering the space. It is worth a quick read; those then looking for a tutorial on how to join Twitter can contact Meaghan Agnew, who oversees our social media, at meaghans@bu.edu.

On to today’s note. Population health is concerned with studying the health outcomes of groups, including the distribution of health outcomes within these groups. Our dominant methodological approach in public health—reducing systems to their simplest component and applying principally linear methods to understand the relation between potential causal factors and health indicators—has yielded substantial public health success. But there is also growing appreciation of the challenges of this approach, particularly as we globally move away from simpler unicausal disorders to complex disorders with multiple causes that have shown themselves to be resistant to the identification of simple causes, or simple solutions.

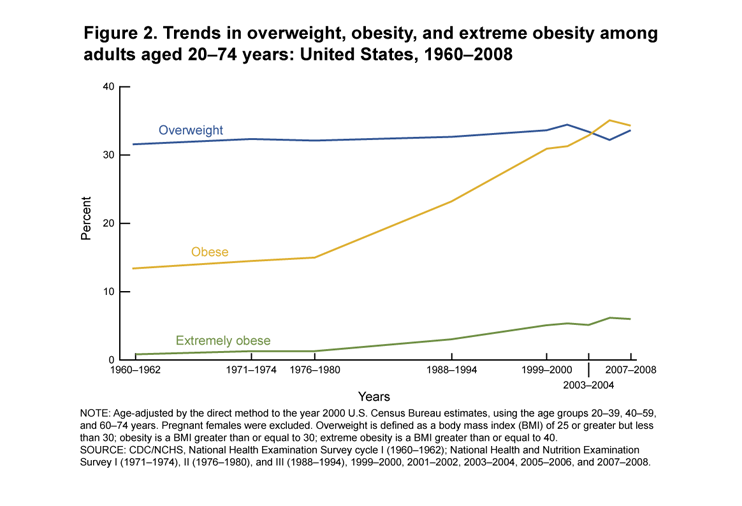

By way of illustration, obesity increased in prevalence by more than two-fold from 1960 to 2008 (see Figure 1) and has settled into a role as an intractable public health problem. Obesity is linked to several of the most common preventable causes of death, including diabetes, coronary heart disease, and some types of cancers. In 2008, an estimated $147 billion was spent on obesity in the United States alone. The unflagging course of what is truly a global epidemic suggests that despite widespread investment in research and public health campaigns, standard public health approaches have failed to yield effective interventions. In the conclusion of “Changing the Future of Obesity: Science Policy and Action,” the authors write, “The obesity epidemics in countries throughout the world are driven by complex forces that require systems thinking to conceptualise the causes and to organise evidence needed for action.”

Ogden, C. L., & Carroll, M. D. (2010). Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–1962 through 2007–2008. National Center for Health Statistics, 6, 1-6.

嗨

It is becoming increasingly clear that these approaches have a place in public health thinking and in quantitative public health analysis for conditions that extend well beyond infectious disease, including conditions such as obesity that have displayed classic hallmarks of complex conditions that are resistant to simple analytic and policy approaches.

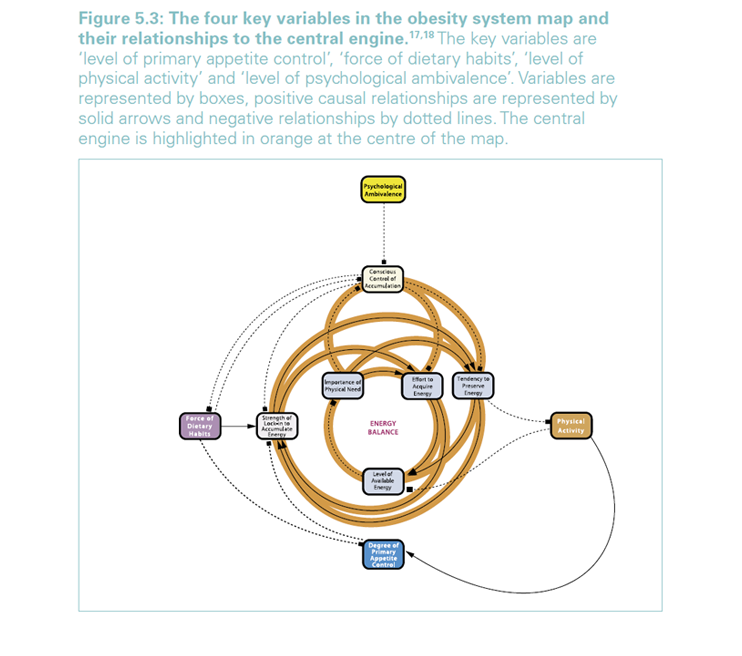

Responding to the potential in this approach, and continuing with our example, the UK government’s foresight project published a strategic plan for responding to obesity in the UK over the following 40 years. Taking a complex systems approach to obesity, the researchers modeled the “central engine” of obesity as a function of four key variables: level of primary appetite control, force of dietary habits, level of physical activity, and level of psychological ambivalence. As Figure 2 illustrates, these four variables and their subcomponents represent a complex system of causal influences. Yet this central engine is but a small subset of a much larger complex system, which includes such disparate domains as social psychology, food production, and activity environment.

http://www.foresight.gov.uk/OurWork/ActiveProjects/Obesity/KeyInfo/Index.asp

This approach has led to novel insights around the determination of obesity and a growing focus on the conditions that produce obesity, including, for example, walkability of neighborhoods and availability of healthy foods.

There is a role for complex systems approaches in a broad range of other public health challenges beyond obesity. For example, efforts at cutting cigarette nicotine levels can lead to compensatory smoking, illustrating the unanticipated consequences of particular system perturbations if we do not fully consider the system’s dimensions and interrelations. Other illustrations of the centrality of complex systems to public health thinking include anti-retroviral therapy prolonging the lives of HIV carriers but potentially leading to HIV spread due to lower risk perception; antibiotic overuse worsening pathogen resistance; antilock brakes leading to more risky driving; and use of protective headgear in football failing to decrease concussion due to risk compensation.

在

Galea, S., Riddle, M., & Kaplan, G. A. (2010). Causal thinking and complex system approaches in epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39(1), 97-106.

In sum, a complex systems approach is built on a recognition that population health is the product of a complex system of interrelated factors that produce health through dynamic processes characterized by inter-relations, non-linearity, reciprocity, and emergence. While system simplification can yield important insights that can inform public health efforts, increasingly we are recognizing unintended consequences of over-simplification of complex systems, suggesting that a complex systems conceptual lens, perhaps supplemented by complex systems analytic approaches, can be a useful part of our public health armamentarium. It has been fascinating watching the increasing adoption of these methods in quantitative public health analyses during the past decade; I look forward to emerging theoretical and empirical work that can further illustrate when these methods are a useful part of our suite of methods for population health science.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: Gregory Cohen MSW contributed to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: /sph/category/news/deans-notes/