Transportation and the Health of Populations.

Last week, we saw two examples of how political policies affect the health of populations. The Congressional Budget Office determined that the healthcare bill currently under consideration by the Senate will strip 22 million people of coverage; the Supreme Court ruled to partially uphold the Trump administration’s ban on travelers from six Muslim-majority countries. Each of these policies, crafted at the highest level of government, has profound implications for well-being, and argues for our continued engagement with politics. For today’s note—in keeping with this theme—a look at how decisions around transportation policy shape health.

Last week, we saw two examples of how political policies affect the health of populations. The Congressional Budget Office determined that the healthcare bill currently under consideration by the Senate will strip 22 million people of coverage; the Supreme Court ruled to partially uphold the Trump administration’s ban on travelers from six Muslim-majority countries. Each of these policies, crafted at the highest level of government, has profound implications for well-being, and argues for our continued engagement with politics. For today’s note—in keeping with this theme—a look at how decisions around transportation policy shape health.

Our health is, in large part, a product of our choices. What we choose to prioritize, based on our values and the knowledge available to us, either pays health dividends as a product of smart investment in the social, economic, and environmental conditions of health, or, at times, undermines well-being—or fails to move the needle on health at all—when our investment ignores these conditions. I will write more on the role of choice in public health in a future Dean’s Note. For today, I will use transportation as a case-in-point. Transportation embeds societal decisions, creating health consequences that are a direct result of the choices we make when dealing with a sector that we do not typically consider a “health sector.”

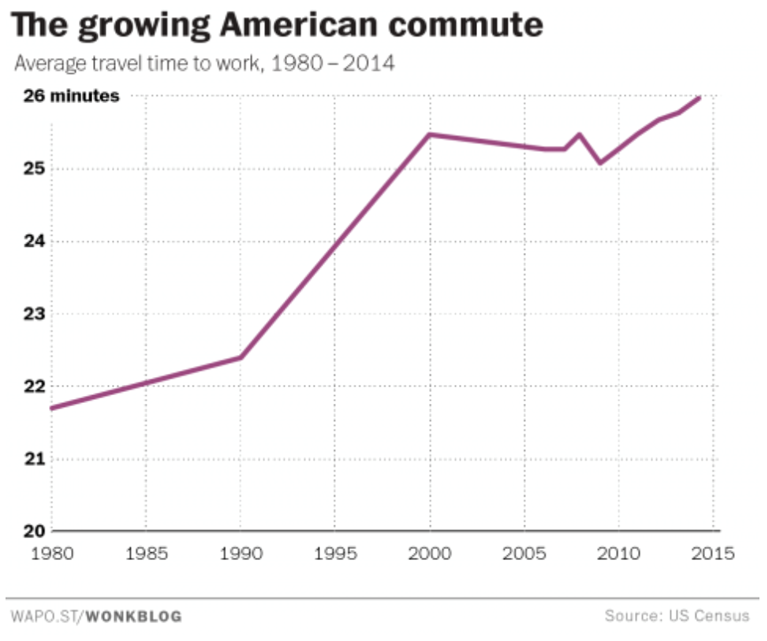

Transportation is a ubiquitous presence in our lives. We are constantly in a state of getting-to-places, whether our destination is work, school, errands, attending to family commitments, or leisure travel. Take just one subset of this trend—commuting to work. There were more than 139 million US commuters in 2014. And their time spent in-transit is only increasing. The average US worker takes 26 minutes to travel to their place of employment, nearly 20 percent longer than the average 1980 commute of 21.7 minutes (Figure 1).

Ingraham C. The astonishing human potential wasted on commutes. The Washington Post. February 25, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/02/25/how-much-of-your-life-youre-wasting-on-your-commute/?utm_term=.ec4549c86b5e Accessed May 30, 2017.

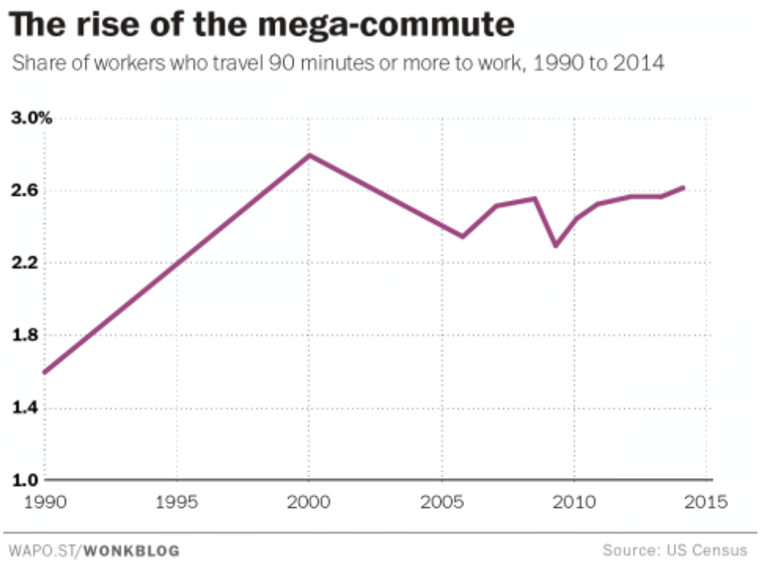

In 1990, the Census began tracking the number of Americans who commuted 90 minutes or more each day, 1.6 percent of workers that year. In 2014, the number of these “mega-commuters” had risen to 2.62 percent (Figure 2).

Ingraham C. The astonishing human potential wasted on commutes. The Washington Post. February 25, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/02/25/how-much-of-your-life-youre-wasting-on-your-commute/?utm_term=.ec4549c86b5e Accessed May 30, 2017.

All of this commuting time adds up. In 2014, commuters spent a total of 1.8 trillion minutes “on the go.” A daily 26-minute commute amounts to a full nine days per year in-transit. A daily 90-minute commute amounts to an entire month—31.3 days (Figure 3).

Ingraham C. The astonishing human potential wasted on commutes. The Washington Post. February 25, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/02/25/how-much-of-your-life-youre-wasting-on-your-commute/?utm_term=.ec4549c86b5e Accessed May 30, 2017.

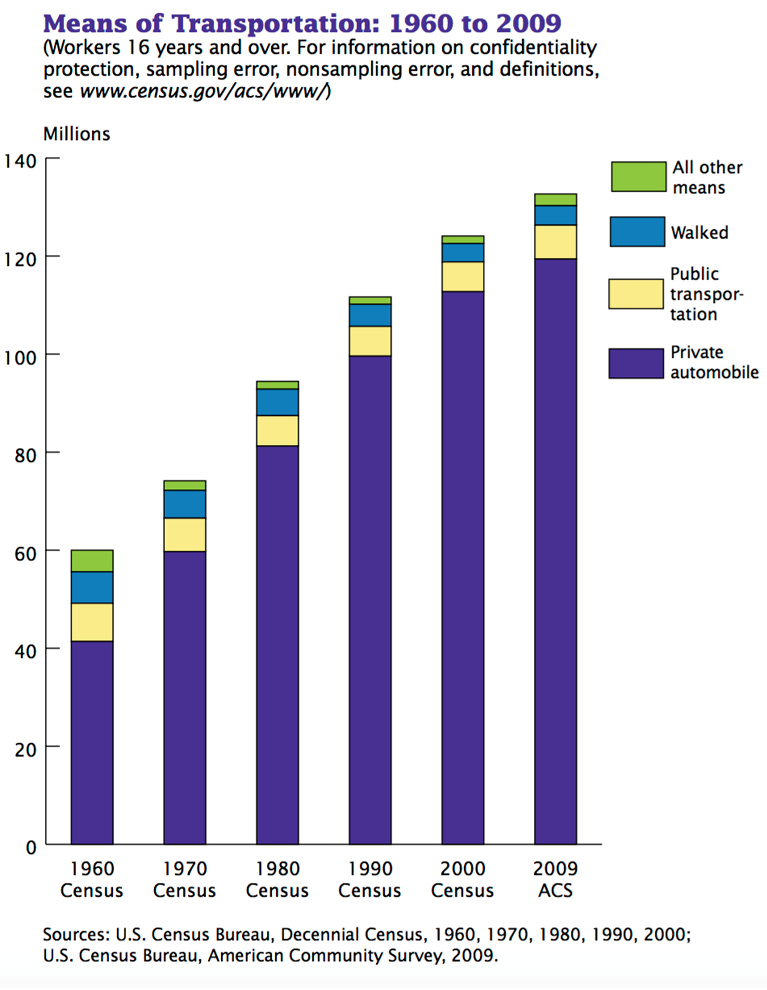

Most of this commute time is spent in a car, rather than on a bus, train, bicycle, or on foot. In 2009, more than three-fourths of US workers drove alone to work (Figure 4).

McKenzie B, Rapino M. Commuting in the United States: 2009 American Community Survey Reports. US Census Bureau; Washington DC: 2011. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2011/acs/acs-15.pdf Accessed May 30, 2017.

Given how much time we spend traveling, it is not surprising that transportation shapes our health. It does so in three key ways—through its effect on the mind and body of travelers themselves, through its effect on people who live near the pollution of major transportation routes, and through its potential to broaden or limit access to opportunities and resources, especially for disadvantaged populations.

Fi

Second, transportation infrastructure shapes health through its potential to increase the risk of pollution exposure for certain groups. Minorities and populations at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder are at a disproportionate risk of exposure to traffic-generated air pollution, which can lead to health problems like asthma. In 2010, 3.1 percent of US whites were found to live within 150 meters of a major highway, compared to 4.4 percent of blacks, 5 percent of Hispanics, and 5.4 percent of Asian/Pacific Islanders. The relationship between race and transportation is particularly long and complex. Throughout our country’s history, government-funded highways have divided or isolated minority neighborhoods, curtailing opportunity for residents of these communities, and facilitating the de facto housing segregation we see to this day.

Third, transportation can play a central role in determining socioeconomic mobility, influencing access to everything from education to quality food. When these resources are not immediately available in a neighborhood, being able to get to them using affordable, reliable transportation can be a significant asset to low-resource populations. Likewise, lack of transportation can further entrench the disadvantages of low socioeconomic status.

如果

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: /sph/tag/deans-note/