Why Governments Must Protect and Invest in Green Natural Capital for a Sustainable Future

By Yan Wang and Yinyin Xu

Three years since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple extreme weather disasters have pushed millions of people to the brink of hunger and poverty. Progress in achieving the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has been rolled back in many countries due to overlapping crises, or ‘polycrises’ in the spheres of public health, climate change and humanitarian crises caused by war.

Crises can provide opportunities to reflect on humankind’s relationship with nature, and to rethink development strategies by going back to basics.

A country needs at least three kinds of capital for development: human capital, natural capital and produced capital. Natural capital can be further divided into renewable and non-renewable natural capital. In the past, economists stressed the importance of accumulating physical or productive capital, while human capital was underinvested in and natural capital was overly exploited. In this day and age, natural capital is of the highest importance and there is an urgent need for green transformation to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and to protect the planet.

In our new working paper published by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, we explore the nexus between natural capital, CO2 emissions and economic development, with a special focus on the role of development finance. In this working paper, we define green transformation as a process of building-on and upgrading nations’ existing green natural capital (GNK) based on the World Bank’s natural capital classification, such as land, forest, fisheries and protected areas, to add to their value for resilience and to prevent CO2 emissions. We evaluate the extent to which development finance from different sources, including China, has an effect on emissions, natural capital and economic development in developing countries.

Consistent with earlier work, we find an ‘N-shaped’ relationship between CO2 emissions and levels of per capital income, and a negative association between GNK and CO2 emissions, indicating a robust “biological carbon sequestration” effect. Furthermore, external finance (including China’s) is associated with rising incomes and lower carbon emissions, but has a detrimental impact on GNK. Multilateral development banks have no significant impact on CO2 emissions or GNK, implying they may ‘do no harm,’ but are not working to advance sustainable development.

Recognizing the unequal distribution of countries’ contributions to cumulative CO2 emissions, climate risks and damages, policymakers in developing countries are seeking a balance between growth, poverty reduction and sustainability through green transformation. The question is which sectors can help green structural transformation without hurting prospects for economic growth. To assess this unknown, we placed GNK at the center of our analysis, utilizing a novel dataset for 96 emerging market and developing economics (EMDEs) and a simultaneous equation model (SEM).

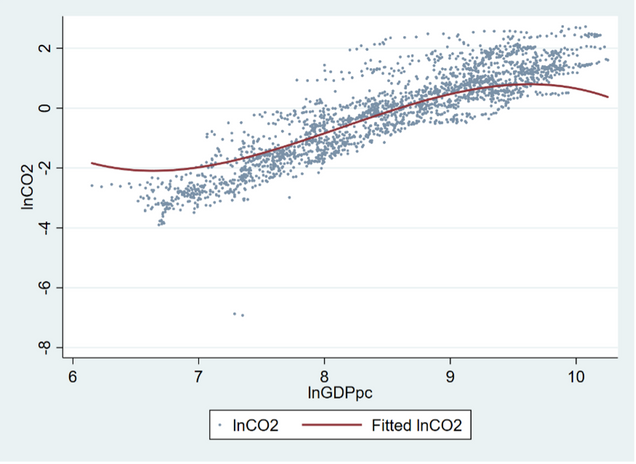

First, our results confirm an inverted-N relationship between the CO2 emissions and per capita GDP, where the emissions drop until the first threshold of income level and grow sharply until the second threshold and finally decrease again. This pattern is validated by regressions with a panel data for 96 EMDEs from 1995-2018, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: An Inverted N-Shaped Relationship Between the CO2 Emissions and GDP per capita

Second, building on and upgrading a nation’s existing GNK, such as land, forest, fisheries and protected areas, could have a “biological carbon sequestration” effect on CO2 emissions, that is, the natural ability of ecosystems to store carbon. This means that GNK has the potential to contribute to carbon reduction in developing countries through ways other than expensive carbon capture and storage techniques.

Third, we find that economic agents in developing countries typically use GNK in early stages of economic growth for agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing and manufacturing, so GNK declines as the economy grows. Only when the economy reaches a certain phase of development does the government start to invest in GNK.

The role of development finance was largely neglected in previous EKC research in the Global South, although development finance is essential to many developing countries for their development pathway. In regression analyses on the impacts of various forms of external finance on GNK, we find that:

- External finance is associated with income growth, wherein foreign direct investment (FDI), bilateral and multilateral lending all have significantly positive associations with GDP per capita.

- FDI and bilateral official lending were both found to reduce carbon emissions.

- FDI and bilateral official lending worsens GNK, indicating certain degrees of over-exploitation, such as de-forestation, over-grazing and over-fishing and even desertification in some cases.

- We found no evidence that multilateral lending has significant impacts on carbon reduction or GNK accumulation, neither harming nor enhancing the local environment.

- Chinese development finance in the energy sector is associated with lower CO2 emissions but has a negative impact on GNK. Despite a large coal portfolio, China’s significant investment in hydropower and some renewable sources may account for the lower emissions. The negative impact of Chinese development finance on GNK has been anticipated and is likely a result of the location of Chinese development projects in relatively more ecologically sensitive areas and the lack of compulsory environmental risk management policies.

These results indicate that GNK is a neglected area of investment by multilateral and bilateral development financiers. Investing in and augmenting the value of forests, land, fisheries and protected areas could reduce CO2 emissions and improve people’s incomes and welfare.

Investing in GNK requires long term “patient capital” supported by strong and compulsory environmental risk management frameworks which can be provided by multilateral and bilateral development banks, as well as the host countries’ fiscal resources and national development banks. An advantage is that GNK investments are labor-intensive, which will consequently create employment and promote rural development and poverty reduction. In practice, these investments tend to have a clear socio-economic and environmental goal to achieve, making them an ideal match for life-cycle environmental management frameworks or systems based on a common understanding among bilateral and multilateral creditors.

Investments in GNK are not as risky as investments in infrastructure, like power generation and transportation, which are highly capital-intensive and slow to build. EMDEs can invest in GNK accumulation without incurring large amounts of debt, and subsequently turn these investments into priority areas for boosting sustainable development.

Governments and development banks may consider various forms of incentive schemes, such as ecological service subsidies and working with local communities to invest in agriculture (crop land), forestry, animal husbandry (pastureland), fishery and protected areas and related small-scale and affordable renewable energy projects, i.e., mini grids, agricultural biomass and so on.

In the face of a looming debt crisis, any debt relief provided by the multilateral and bilateral development banks will not be enough to help indebted countries achieve equitable recovery and build resilience. While providing more development finance through grants might be one of the major contributions of development banks to the current debt crisis, channeling the limited development resources to the most needed aspects, i.e., human capital and GNK, will be even more important.

*

Read the Working PaperYinyin Xu is graduate student at the Graduate Program in Regional Science at Department of City and Regional Planning, Cornell University.

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.