Access to Family Planning Services is Key to Improving Contraceptive Use and Birth Spacing

By Emanne Khan

Family planning and access to contraception protect the well-being of mothers and children by reducing the risks of unintended pregnancy, infertility, infant mortality and sexually transmitted diseases. Unmet need for family planning is a major issue in low- and middle-income countries, with the Guttmacher Institute estimating that a staggering 225 million women in developing regions do not have access to contraception, despite currently not wanting to become pregnant.

Timing is an especially important component of family planning, and contraception can help women more effectively time and space births. Since 2005, the World Health Organization has recommended women wait at least 24 months after a live birth before becoming pregnant again. When a woman becomes pregnant before the 24-month mark, she faces higher risk of miscarriage, premature birth and both infant and maternal mortality. Recent data shows that in low- and middle-income countries, many births are occurring at short intervals that may jeopardize the health of both mother and child.

How would improving access to family planning services impact women’s contraceptive use and birth spacing? To find out, Mahesh Karra and four colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial known as the Malawi Family Planning Study with 2,143 married women aged 18-35 from Lilongwe, Malawi, who were either pregnant or had recently given birth at the time of recruitment. Women in the trial were randomly assigned to an intervention group or a control group. The intervention group received four family planning services over a two-year period, including counseling sessions, free transportation to a clinic, free services at the clinic, financial reimbursement for services obtained elsewhere and treatment for contraceptive-related side effects.

A new journal article summarizes the Malawi Family Planning Study and its major findings. Karra and coauthors note that the small number of previous studies assessing the impact of family planning interventions in Egypt, Bangladesh and Burkina Faso produced mixed results and did not discuss how family planning interventions impact birth spacing.

Baseline contraceptive use among married women of reproductive age in Lilongwe is quite high (at around 58 percent) compared to other developing countries. However, approximately 19 percent of women in Malawi report having an unmet need for family planning, and short birth spacing is prevalent. Karra and colleagues subsequently designed their intervention to address common reasons why women in developing countries do not use family planning services, including lack of knowledge, lack of access, opposition to use and fear of side effects.

Recruiting women to take part in the trial involved selecting neighborhoods in Lilongwe, screening households for eligible women and informing women of their eligibility. Once participants were selected, they were given a baseline survey to determine their current family planning practices and then assigned to either the intervention or the control group.

In the time between the baseline survey and the one- and two-year follow up surveys, women in the intervention group received:

- A family planning information package and up to six private counseling visits at or near their home with family planning counselors who were trained by the Ministry of Health’s Reproductive Health Directorate;

- Free transportation service to a designated high-quality family planning clinic with low waiting times;

- Free family planning services at the designated clinic or financial reimbursement for any family planning services received at other clinics;

- Free phone consultations with a doctor and referral services along with reimbursement for treatment costs if women experienced any side effects related to use of family planning.

Meanwhile, women in the control group received information about the nearest family planning clinic and were only re-contacted during the follow-up surveys. As for the role of husbands during the intervention, Karra and coauthors note that the study was not designed to address social norms about male views of family planning, and the extent to which a woman wanted to involve her partner in the counseling and intervention was her choice.

Better access, better outcomes

The Malawi Family Planning Study yields several major findings:

- Contraceptive use after two years of exposure to the intervention increased by 5.8 percentage points, mainly through an increased use of contraceptive implants.

- The intervention group’s risk of pregnancy was 43.5 percent lower 24 months after their initial birth.

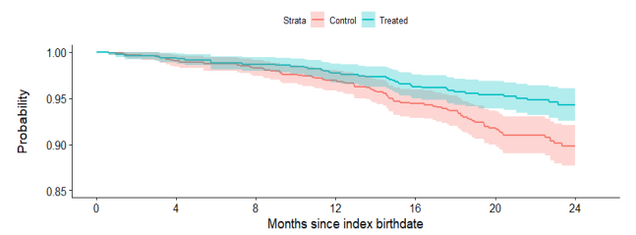

Figure 1 below presents a Kaplan-Meier survival plot of the probability of not having a short pregnancy interval for women in the control versus intervention groups. A probability of one on the left axis represents no risk of short pregnancy interval. The fact that the treatment line is consistently above the control line shows that throughout the trial, women who received the family planning intervention were at lower risk of becoming prematurely pregnant than their counterparts in the control group.

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier Survival Plot, Probability of No New Pregnancy within 24 Months after Birth

What factors are behind the increase in contraceptive use among women in the intervention group? In their responses to the surveys, women reported preferring contraceptive methods that are effective, easy to use and do not require re-supply or revisits to the clinic—hence why the increase was driven by implant use.

The Malawi Family Planning Study faced several limitations, including attrition of women between surveys and the fact that the researchers are not able to causally distinguish the effects of the individual components of the intervention package. Furthermore, the intervention was intensive compared to interventions used in other countries, complicating generalizability of results.

Nevertheless, Karra and coauthors’ findings demonstrate strong positive effects of expanding access to family planning, particularly on contraceptive use and birth spacing. Evidence from the study can contribute both to the design of future family planning programs and to the debate about how such programs can improve health outcomes and longer-term development more broadly.

Read the Journal Article