Devising Ways to Measure Unmet Need in Family Planning: A Thought Experiment

By Mahesh Karra

Unlike many domains in health, the provision of high-quality family planning services is not only measured by the achievement of good reproductive health outcomes, but also considers the objective of helping women and couples maximize a complex and evolving set of preferences around future fertility and well-being.

For this reason, the demand for (and use of) contraception differs from most other interventions in health; while one can assume that individuals have a demand for health interventions that reduce their risk of morbidity and mortality, the same cannot be said for the demand for contraception since women and couples may, in fact, want to become pregnant at different points over their lifetimes. As a result, it has become incumbent on family planning and reproductive health programs to:

- Demonstrate that a demand for contraception and family planning exists; and

- Measure the extent to which this demand for contraception is met through use.

To this end, the concept of unmet need, which aims to estimate the proportion of women who want to delay or stop childbearing but are not using contraception, plays a fundamental role in family planning research, evaluation and advocacy and has received significant attention from academics in of reproductive health, human rights and reproductive justice, economics and demography.

In a recent working paper, I review the concept of unmet need and propose a new approach to more effectively measure it with routine data.

Unmet need: current definition and measurement challenges

Although the underlying concept of unmet need, the non-use of contraception among women stating a desire to avoid pregnancy, appears to be straightforward, its measurement is problematic and complex and has undergone multiple revisions in recent decades.

In its latest iteration, unmet need is calculated as the proportion of sexually active women of reproductive age who want to either limit or space their next birth for at least two years, but are not using any contraceptive method. While this revision is a significant simplification from previous versions, measuring unmet need still imposes a heavy data burden – up to 15 items from survey responses are needed to capture a range of indicators related to:

- A woman’s potential exposure to the risk of pregnancy;

- Her sexual activity;

- Her physiological capacity to become pregnant (fecundity); and

- The reliability of a woman’s retrospective reporting of her preferences to space and limit births.

The categorization of women into whether they have a met need, unmet need, or no unmet need under this revised definition continues to be a challenge. Figure 1 below presents a flow diagram of the classification algorithm that is currently used by the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).

Figure 1: Current Methodology for Unmet Need Classification, DHS

Source: United States Agency for International Development, 2012.

Over the years, a number of methodological limitations related to the measurement and estimation of unmet need have been highlighted by scholars and practitioners alike. Perhaps the most problematic feature of the current measure, however, is its reliance on women’s reported fertility preferences, and particularly the measurement of women’s wantedness of births through survey questions that ask them to recall their preferences when they became pregnant. This is ascertained by asking women “At the time you became pregnant with [name of the most recent birth], did you want to become pregnant then, did you want to wait until later, or did not want (more) children at all?” By asking women to retrospectively reflect on past births, this approach suffers from ex-post rationalization bias, where women are more likely to express reluctance to declare a past pregnancy or birth as unwanted, and particularly when the past birth of interest refers to a child who is alive.

More generally, the reliance of unmet need on women’s stated (reported) preferences as a proxy for their true (revealed) fertility preferences is itself problematic. This is because respondents are faced with hypothetical choice problems that attempt to elicit their preferences over alternatives that may not be applicable to them. As a result, respondents may not make the same choices in a hypothetical situation as they would in real life. In the case of fertility, this “hypothetical bias” implies that respondents may be willing to state a preference for more or fewer children when asked in a survey than they would actually prefer if the opportunity to realize this preference were to truly present itself.

On the other hand, a more robust measure of a woman’s revealed fertility preferences may be more informative about her true underlying fertility preferences and, in turn, may reveal her hidden demand for contraception.

Conceptualizing unmet need: a step back and a way forward

The primary objective of unmet need is to estimate the proportion of women who are not using contraception, but who have a preference for limiting or spacing births.

Taking a step back, unmet need can be understood by the following thought experiment. Say the current contraceptive prevalence refers to the proportion of women who currently use contraception. Now say that the ideal contraceptive prevalence refers to the proportion of women who would use contraception in a world where their fertility preferences could be fully realized without cost. In this ideal environment, women would face no barriers, costs, or constraints of any kind to using contraception and to exercising their preferences for limiting and spacing births. In this environment:

- Women would be able to completely control their family planning and reproductive health decisions and would have full, free and informed choice over their contraceptive use, non-use and type of use (e.g. method type);

- Women would be fully capable to realize any changes to their preferences that they make over fertility and childbearing (they can change their minds at any time without constraint); and

- There are no social, structural, emotional, or physical barriers that women face to making decisions over their contraceptive use and fertility. Women would have complete support from their partners, families and communities on all reproductive decisions over their lifetimes.

Unmet need for contraception can be calculated as the difference between ideal contraceptive prevalence and current contraceptive prevalence.

When thinking about how to actually calculate this difference, it should be noted that while current contraceptive prevalence is straightforward to estimate with reported survey data, the identification of ideal contraceptive prevalence is, by construction, hypothetical.

To estimate ideal contraceptive prevalence, previous estimators of unmet need have relied on women’s stated fertility preferences through wantedness of births, and then inferred the extent to which their contraceptive use concords with these preferences.

In the working paper, I propose the inverse: first, by inferring the ideal environment under which all fertility preferences can be realized and then by estimating the contraceptive prevalence in this environment. This approach hinges on the premise that the contraceptive prevalence under this ideal environment would reflect women’s true (revealed) fertility preferences and, by extension, demand for contraception. If such an environment could be identified and estimated, then this approach would have a distinct advantage over traditional estimators in that it requires no direct and problematic measures of preferences.

As an attempt to identify this “ideal” environment, imagine that contraceptive prevalence under an “ideal” environment would be the prevalence among the sub-population of women who are situated in “ideal” conditions in which they have full, free, informed choice over their contraceptive use and are capable of acting on their preferences to the greatest possible extent.

To identify this “ideal” sub-population, narrow down the sample of women based on characteristics that are more likely to signal their level of contraceptive and reproductive empowerment. A key advantage of this approach is that women who live in these selective environments can be identified using routine survey data (e.g., DHS). Additionally, similar approaches have been utilized in child growth and development, where past studies constructed “ideal” reference populations and have conducted comparative analyses to identify gaps in child growth and stunting relative to the reference group.

Testing a new unmeet need measure and main findings

To undertake this new approach to estimating unmet need, data on 2,073,523 women from 80 DHS surveys covering 56 countries from 2010-2019 was analyzed and a subsample of women who meet the following five criteria was identified:

- They belong to the highest wealth quintile, a proxy for their socioeconomic status.

- They are either currently married or have been sexually active.

- They have attained at least a tertiary level of schooling.

- They know at least one contraceptive method, which also serves as a proxy for being informed about family planning and reproductive health services.

- They do not report distance to a facility as being a significant problem in their access to health care.

When filtering the full sample of women by these five criteria, a final “ideal” sample of 55,318 women from 52 countries across 73 DHS surveys (2.71 percent of the full sample of women) was identified.

There were significant differences between women from the full sample and women who were selected to be from ideal environments. In particular, women from ideal environments are:

- More likely to reside in urban settings.

- More likely to be older, on average.

- Have fewer children, on average.

- Are married to husbands/partners who are significantly more likely to have a tertiary level of education.

- Are more likely to earn as much or more than their husbands/partners.

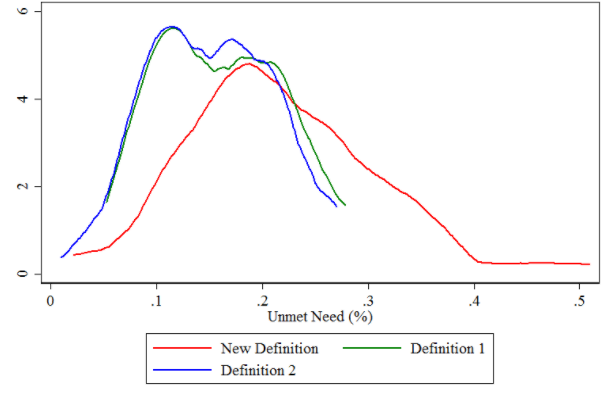

The newly calculated measure of unmet need was then compared against the two measures of unmet need that are currently used by the DHS. Unmet need using the new measure is, on average, five to six percentage points (30 percent) higher than the two standard measures of unmet need. Moreover, the distribution of unmet need measures using the new approach is wider, yielding more extreme estimates of unmet need on both the lower and higher end, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Kernel Density Plots, Unmet Need Across Definitions

Source: Karra, 2021.

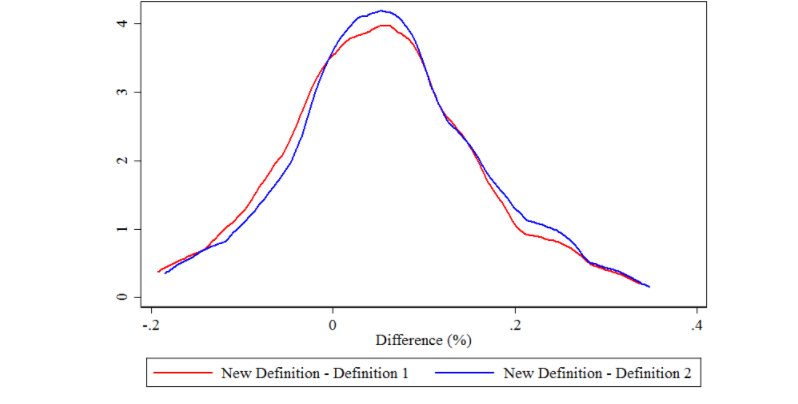

Wide variation was observable across the data; in some surveys, the new approach estimated a significantly higher (up to 30 percentage points) unmet need than what is currently estimated, while in other cases, our approach yielded significantly lower estimates (up to 20 percentage points) of unmet need, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Kernel Density Plots, Difference between the New and Old Unmet Need Measure

Source: Karra, 2021.

Final thoughts

Unmet need has been a key indicator in family planning and reproductive health for more than four decades. It is an indicator that holds significant policy and programmatic weight and serves an important role in advocacy, resource allocation and agenda setting in family planning.

Previous reviews of unmet need have raised a key question: “What is desirable contraceptive coverage in the ‘perfect contracepting’ society, and what principles should guide the answer to this large question?”. This analysis takes a first step in answering this question by estimating what contraceptive coverage would look like in an environment where women have the capability to “perfectly contracept” if they choose.

Given that this approach questions the value of directly asking about women’s fertility preferences through surveys, the findings call for a critical review of existing surveys and a reprioritization of survey content that is currently a part of large-scale and costly data collection efforts, like the DHS. The analysis also specifically calls for the substitution away from the use of problematic fertility preference questions that are known to be biased from the onset and towards a wider and more inclusive range of observable indicators that would effectively measure reproductive empowerment, family planning access and well-being.

In the absence of any changes to the current data collection practices, future efforts should be encouraged to test a wider range of factors that capture women’s ideal reproductive health environments to determine the extent to which ideal contraceptive use, and by extension unmet need, are sensitive to these choices.

Read the Working Paper