REVIVING LOCAL JOURNALISM

COM faculty, students and alums are filling the void in a changing industry

在马萨诸塞州议会大厦四楼后翼的深处,有一个456号房间,专为记者保留。

“There used to be bitter fights over every square inch of territory, because every newspaper wanted to have someone with a desk at the Statehouse,” says Chris Daly, a professor of journalism and Statehouse bureau chief for the Associated Press from 1982 to 1989.

“The AP had four or five people. The Christian Science Monitor had a person whose only job was to cover state government, the Lowell Sun, the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune, on and on and on, and we were all jammed in there,” he says. “Now, that room is empty and cavernous—there are echoes. There’s hardly anybody working there.”

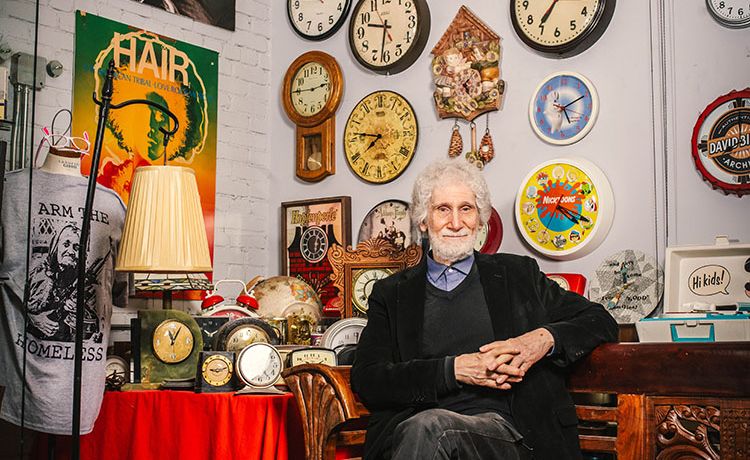

Jerry Berger, a lecturer in journalism, was the Statehouse bureau chief for the news service United Press International around the same time Daly was there. He now heads COM’s Statehouse Program, which provides students—mostly seniors and graduate students—the opportunity to report on politics for more than a dozen news outlets around Massachusetts. Though a 2022 Pew report found that the number of statehouse reporters has gone up across the US since 2014, it also found there are fewer working the beat full-time. “Part-time beat reporters can’t do the job as well as someone based in the building full-time who can hear gossip in the coffee shop and hallways and drop by offices to chat with lawmakers and their staffs,” Berger says. He adds that virtually every publication that his students work with used to have its own Statehouse reporter.

Today, COM’s Statehouse Program is the largest news operation covering Beacon Hill. And that’s just one of the programs that give COM students journalism experience while helping provide coverage of important local news in an industry that’s been contracting for decades.

At its most extreme, that contraction has led to the creation of news deserts—areas without local, independent journalism. A February 2022 Columbia Journalism Review article, “Our Local News Situation is Even Worse Than We Think,” called the deterioration of local journalism “a truly bleak picture,” and cited a US Bureau of Labor Statistics report that shows a 57 percent decline in newspaper newsroom employees since 2004.

“This is a great time to be a corrupt politician,” says Daly, an expert on the history of journalism and author of Covering America: A Narrative History of a Nation’s Journalism (University of Massachusetts Press, 2012). “There’s hardly anybody left anymore who’s studying these things and watching, and who knows how to read a budget.”

FAR-REACHING CONSEQUENCES

A 2022 report from Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism Local News Initiative provides a grim statistic: more than 20 percent of Americans live in a news desert or a community at risk of becoming a news desert. Papers have shut down because of a loss in subscriptions and ad revenue as people have turned to social media and other online platforms. But many of these news deserts exist in low-income, rural areas that also lack reliable internet access. As the problem spreads, even affluent suburbs are losing their papers as media conglomerates merge or close more papers. “Seventy million people live in the more than 200 counties without a newspaper, or in the 1,630 counties with only one paper—usually a weekly—covering multiple communities spread over a vast area,” the report adds.

The regionalization and homogenization of newspaper coverage has even been occurring in Massachusetts. “What’s happening is, as the industry is getting hollowed out by the hedge fund owners, local coverage is suffering. I can point to two examples: the Marlborough Enterprise and the Hudson Sun,” says Berger. After a series of consolidations, both papers became part of Gannett’s Wicked Local in the 2010s. They went from publishing daily to publishing weekly and then, in 2021, they were shuttered. He remembers the day his hometown paper, the Brookline TAB, also part of the Wicked Local network, ran a story about how federal American Rescue Plan Act money was being used for a road repair project—in Taunton, more than 30 miles away.

Many papers in Massachusetts have stopped covering local topics such as school committees and select boards. “Reporters are given regional jobs and regional issues—which have their place—but the role of local journalism is to tell people what their local elected officials are doing, what the school lunch menu is and what the high school sports teams are doing. That’s going away,” Berger says.

As newsrooms shutter, there has been a spiral of other negative effects, says Daly. The decline in an area’s local news presence has been linked to lower voter turnout. It also has implications for those who do vote. “In places where there is no local news, people are paying more and more attention to national news, and they are, in the process, becoming more and more politically polarized,” he says.

Indeed, a 2020 study by researchers from MIT, Sciences Po Paris and Yale, “Media Competition and News Diets,” connected the decline in local journalism to “increasingly nationalized news diets” and “a decrease in split-ticket voting across Congressional and Presidential elections.”

“It’s easier to hate someone who is an abstraction or a brand name, and represents people 1,000 miles away from you,” says Daly. “When you are talking about local politics, it’s a different ethos. It’s less emotional and more practical—more focused on solving common problems. Do we need a new school? Who’s going to pay for it? Where should it go? These are not the hot button issues that really fuel partisanship.”

Though the situation is dire, both Berger and Daly have hope for the future of local reporting, especially when they consider the work their students produce.

[Students] see the joy on people’s faces knowing the public will learn about their efforts, and they see the surprise on city officials’ faces when they show up to the lesser-known—but often more important— government agency meetings.

—BROOKE WILLIAMS

TEACHING ON-THE-GROUND REPORTING

At COM, undergraduates have the opportunity to learn how to report in a community and cover a beat. Each section of JO 210 Reporting In Depth partners with a different news outlet to produce public interest stories. Previous classes have partnered with WGBH, the Brookline TAB and the Cambridge Chronicle, among others. Each section is limited to 15 students and functions as a newsroom.

Since 2019, COM has partnered with the Boston Globe for one of the sections of JO 210 taught by Brooke Williams, an associate professor of the practice of computational journalism. Students contribute articles to the Globe’s section covering the city of Newton. “When they complete this class, not only do they have professionally published clips, but they also have the skills needed to dive into covering towns and cities far too often lacking robust journalism,” Williams says. “They see the joy on people’s faces knowing the public will learn about their efforts, and they see the surprise on city officials’ faces when they show up to the lesser-known—but often more important—government agency meetings.”

The class is modeling a way that students can be dispatched to cover areas in need of a news presence. “We started to think about how we could partner with professional news organizations to help make up some of the gap,” says Daly, who has also taught sections of JO 210. “I think it’s been a great success.” But, he adds, “I think we can do more, something even more ambitious.” He sees the potential to expand COM’s partnership with the Globe and have students cover city neighborhoods closer to campus, such as Fenway, Allston, Brighton and Jamaica Plain.

While Daly acknowledges these classes won’t solve the problems local journalism faces, he can see how they have made a difference and prepare students to help in areas that are, or maybe become, news deserts. “We need to encourage programs like ours to step up and do more of the real-world professional coverage that urban neighborhoods and their close suburbs need,” he says.

We need to encourage programs like ours to step up and do more of the real-world professional coverage that urban neighborhoods and their close suburbs need.

—CHRIS DALY

REPORTING FOR AMERICA’S FUTURE

Many students who have covered local news while at COM have been inspired to go into the field after graduation. Some have joined nonprofits like Report for America, an initiative launched in 2017 whose primary goal is to stop the collapse of local journalism by pairing emerging journalists with news organizations.

Hannah Schoenbaum (’20) is a corps member with Report for America, covering North Carolina government and politics for the Associated Press out of Raleigh. She says her experience in the Statehouse Program was so transformative, it encouraged her to pursue political journalism as a career. “That program taught me the ins and outs of covering state legislature,” she says. “I fell in love with telling in-depth stories about the struggles that people were facing and the intersections between life and policy in Massachusetts. It was a great training ground.”

Schoenbaum felt a personal connection to Report for America’s mission. “There’s a gap in statehouse coverage across the country. Even in our bureau here, it’s just me and one other statehouse reporter for the AP. One reporter can only do so much,” she says.

Mia Khatib (’22) is also a Report for America corps member in the Raleigh area. She has reported on education, gentrification and affordable housing for the Triangle Tribune, which serves Black communities in North Carolina’s Wake and Durham counties. She didn’t appreciate the impact of local journalism until she began writing for the Tribune. “I’m seeing how so many people in these smaller communities rely on these local papers to find out what’s going on in their communities, what they need to know about where they’re living and what changes are on the horizon that could affect them,” she says.

Khatib and Schoenbaum recently teamed up to mentor students in a journalism class at Riverside High School in Durham, which produces one of the few bilingual student newspapers in the country. The project fulfills a requirement of the program: that corps members engage with the communities they report on. “Most corps members decide to work with a high school journalism class, because we believe so strongly in nurturing the next generation of reporters who are going to heed the call and do the same kind of work that we’re so passionate about,” says Schoenbaum.

GOING HYPERLOCAL

Berger sees a beacon of hope for the future of local journalism in the emergence of more hyperlocal, mostly digital-first, news outlets, such as the Concord, Mass., independent nonprofit newspaper, the Concord Bridge, which launched in October 2022. “It’s just a question of can they find the resources, mainly the financial ones, to be able to pull it off? It’s definitely encouraging,” says Berger.

Another shining example of a newer hyperlocal publication in Massachusetts Berger points to is the New Bedford Light, established in June 2021. The online newspaper, which emphasizes that it’s a free, nonprofit, nonpartisan publication, is funded by individual contributions, partnerships with other media outlets and grants.

We cannot function without a local news presence. We, as the next generation of journalists, have a responsibility to save local journalism.

—HANNAH SCHOENBAUM

Anastasia Lennon (’20), a Statehouse Program alum, is a reporter for the Light who counts among her beats the fishing industry, a topic of great concern to a town that is one of the top commercial fishing ports in the country. “I have a real sense of responsibility,” Lennon says. “I’m there to do a job for the community and make sure certain stories are told—accurately and within the right context.”

Although Lennon didn’t plan on going into local journalism when she started her master’s degree at COM, she’s glad she did. Local reporters know what’s happening in the community and who to talk to about it. They’re also able to build relationships and trust. “Non-local journalists will parachute into a community, and they don’t really know much about it,” Lennon says. “They’re just there to get a story, and it feels transactional.” Community publications also boost civic engagement. “Voter turnout is not the highest in New Bedford, and I think having this local coverage can make a difference,” she says. “It’s also important for holding people in power and making sure they’re held accountable.”

Daly, too, finds the emergence of ultralocal publications and other experimental forms of journalism promising. “I see these little sprouts—like podcasts covering local issues—and I go, ‘I hope that grows and becomes something,’” he says. He’s also encouraged by the role journalism schools across the country play in upholding local outlets. Many college and university journalism programs have followed COM’s model of working with local professional news organizations to improve their reporting capacity. “Students can cover those night meetings, cover protests, cover all kinds of stuff,” he says. “And our students are good at those things. They’re capable and they’re part of the answer.”

Young journalists like Schoenbaum and Khatib believe that the future of journalism is in their hands. “It was instilled in me from day one at COM that local news is so important to our democracy and life as a whole,” says Schoenbaum. “We cannot function without a local news presence. We, as the next generation of journalists, have a responsibility to save local journalism.”