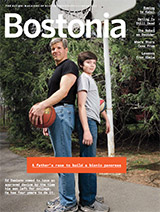

As far back as Jan Egleson can remember, an unseen barrier walled off his father from the world. A World War II naval combat veteran, “he was withdrawn, he was angry, he was unable to really maintain relationships,” says Egleson, a filmmaker and a College of Communication associate professor of the practice, film and television. Attempts at therapy failed, and it wasn’t until his father died that his son, perusing his papers, realized he’d suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Egleson knew a bit about this demon, having directed Medal of Honor Rag, a 1975 play about the illness. His family tragedy, plus the journalism experiences of Brian David Johnson (COM’05) covering the Iraq War’s fallout on small-town New Hampshire, compelled the two to team up to create the graphic novel MWD: Hell Is Coming Home (Candlewick, 2017). Illustrated by Laila Milevski, the book introduces readers to PTSD’s psychic ravages on an Army dog handler named Liz.

MWD got a thumbs-up from Kirkus Reviews, which calls it “a nuanced and carefully composed snapshot of one woman’s postwar struggle to live.” The novel describes the loss of a crucial bond, as Liz returns to New Hampshire from Iraq, grieving the combat death of her dog (MWD stands for military working dog).

If the conceptual edifice of MWD belongs to Egleson, Johnson mortars its bricks with details picked up as a reporter. One of the people he interviewed was a New Hampshire woman whose brother, a marine, had just been killed in Iraq by an improvised explosive device. The sorrow carved into her face helped create the novel’s portrayal of Liz.

“I was the first person to talk to her after she found out her brother was incinerated,” Johnson says. (The disturbing sense that he was invading her privacy helped cut short his newspaper career; today, he’s the publisher of MassDevice.com, a site he cofounded covering the medical device industry.)

Among the real-life details from his reporting that made it into the book: “There was a wrestling team in Salem, N.H., at the high school that had three kids go to Iraq…and all three were killed.”

Although both men have BU connections, they didn’t meet until Egleson, who has directed several movies and numerous TV shows, including Law & Order, became a Pilates student of Johnson’s wife. When the former reporter showed him a teleplay he’d written about his newspaper experience, Egleson asked him to collaborate on a screenplay about a PTSD-afflicted dog handler, a project he’d had in mind for a while.

“PTSD is very hard to get inside,” Egleson says. “But attachment to animals is something that cuts through everything. We all understand it. The loss of a pet is devastating to people.” Johnson liked the plot; he has a sister-in-law who trains dogs, and one of her charges, a German shepherd named Ender, gave its name to the dog Liz adopts in MWD to try to repair her broken heart.

Cowriting proved easy for both authors. Egleson says that “to make films is all about collaborating,” and Johnson acknowledges that his partner helped move him off his journalist’s rigid adherence to linear character development. “Jan was really instrumental in fighting for the character as a real person with different emotional responses that I think were not linear,” he says. “Nobody’s monolithic.”

The book’s Iraq illustrations were drawn as “very realistic, very crisp,” Johnson says, reflecting combat’s heightening of the senses, while the returning vet’s homecoming in New Hampshire has “more earthy, less precise, less elegant images,” befitting the fuzzy confusion of trying to settle back into a more normal life.

“If you look at pictures of soldiers with PTSD,” he says, “you can see that they physically change. Their faces become more drawn as they descend into all the different ways of self-medicating.”

Egleson, with his filmmaking expertise and contacts, says the pair will explore possibilities for turning their book into a movie. As for Johnson, he hopes MWD makes its target audience think harder when a dubious war is debated in the future.

“There are a lot of people who are dealing with the aftermath of a war that was fought on—I think we can say—what were false pretenses,” he says. “But the sacrifice of the soldiers—nothing’s false about that.”

Related Stories

A Different Kind of War Story

COM alum’s Day One was an Oscar nominee

She Was a World War II Codebreaker

BU alum Fran Pearlmutter helped America win the war—and kept it secret for 50 years

MOOC Probes a War You’ve Never Heard Of

Middle East course by BU’s Bacevich coincides with ISIS emergence

Post Your Comment