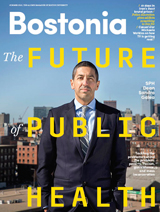

On September 11, 2001, Sandro Galea was at his office at the New York Academy of Medicine on Fifth Avenue when he saw billows of smoke rising from the twin towers.

An epidemiologist and physician who had trained in emergency medicine, he headed for the nearest hospital, Mt. Sinai, to volunteer to treat what he expected would be hundreds of injured people. As it turned out, there were no injured brought to the hospital.

Instead, Galea would make his mark in the aftermath of the disaster as he set out to examine the scope of the mental health consequences of the terrorist attacks. He and fellow researchers found significant increases in both depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the area’s residents—twice the baseline values.

Since then, Galea—who took the helm of the School of Public Health on January 1—has become a leading expert in the health consequences of mass trauma, from Hurricane Katrina to combat in Iraq and Afghanistan.

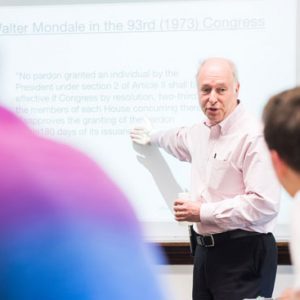

At 43, the former chair of the department of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health has published more than 500 scientific journal articles, many focused on trauma and mental health. Other studies he’s done break new ground in global and urban health, including the role of the urban environment on risk behaviors and the impact of poverty and racial segregation on mortality.

Galea, who grew up on the southern European island of Malta, has chased his own interests across the globe—from northern Canada, where he got his start as an emergency room physician; to Somalia, where he was accompanied by armed guards as a physician with Doctors Without Borders; to New York City, where he has probed trends in drug overdoses, homicides, and HIV/AIDS.

As he begins work as SPH’s third dean, Galea, who earned a master’s degree in public health from Harvard in 2000 and a doctorate from Columbia in 2003 (his MD is from the University of Toronto Medical School), has set his sights on making SPH a place of “relevant research and inspired learning,” he says.

“Schools of public health have a tremendous opportunity to help move public health to the vibrant center of our global society, shaping the broader societal conversation and elevating health as a value that animates public discussion and policy making.”

Bostonia asked Galea about his own experiences and his broader view of public health.

Bostonia: You started out as an emergency physician, then made the transition to public health after a stint with Doctors Without Borders. Why did you make that jump?

Galea: I followed perhaps an atypical path for a public health academic. I initially went to medical school, determined to become a physician who could deal with, well, anything. To that end, I chose to do a combined family medicine/emergency medicine residency in northern Canada. It was terrific training, and it led to my work in the town of Geraldton, about 18 hours north of Toronto. Throughout medical school and residency, I had stints of several months working in remote areas globally, including places like Purok Binao, the Philippines, and the Southern Highlands of Papua New Guinea.

When I left Geraldton, working for Doctors Without Borders seemed like a natural next step. I worked in the Mudug region of Somalia, an area of about 350,000 people. It was a tough time in Somalia, a few years after the fall of [President] Siad Barre. I was doing the medicine I had been trained to do—helping all comers in a tough part of the world, being a clinician in a place where clinicians could make a real difference. It was an immensely gratifying, if challenging, experience.

But it was also then that I became frustrated with the limits of clinical medicine. In Somalia, it became clear to me that as a clinician, I was dealing with “downstream” pathology—working to patch up problems that had started long before I saw the patient. I started thinking that there must be another way, a better way, to make prevention central to a health agenda, a way to change the social structures so that they helped, and did not harm, health. That’s when I decided to go back to school for a master’s degree, and later a doctorate, in public health.

You’ve done a great deal of research into the psychological consequences of mass disasters—from September 11 to Hurricane Katrina. How did you develop an interest in trauma, specifically?

Traumatic events are ubiquitous. Nine out of 10 Americans will experience a significant traumatic event in their lives, and in high-risk parts of America and the world, as many as one in every two people experiences a significant traumatic event annually. Traumatic events have profound and far-reaching implications for health.

In the short term, a substantial proportion of people who experience traumatic events will go on to have mental illness directly linked to the trauma, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and a range of other psychopathologies. Substance use after the experience of trauma is higher. We also know that the risk of physical ailments, including heart disease and lung disease, is heightened after traumatic events.

Importantly, in cases of disasters and mass traumas, we know that these risks are increased in large populations—not simply among those who are most directly affected by these events. Increasingly, we also realize that the consequences of traumatic events do not depend only on the trauma itself. Childhood experiences, even in utero exposures, interact with the traumatic event to produce health outcomes.

You’ve been especially interested in the social determinants of health, the role of the urban environment in health outcomes. How do social factors stack up to behavioral and physiological factors in health?

Disciplinarily, I am a social epidemiologist. Social epidemiology is centrally concerned with how social factors, at multiple levels of influence and across the lifespan, shape the health of populations. This work has led me to explore factors like poverty and racial residential segregation as drivers of population health. Much of that work has been in the context of urban environments. One of my books, Handbook of Urban Health: Populations, Methods, and Practice, published in 2005, was one of the first to establish urban health as a disciplinary focus.

At core, I think that social factors are the foundational drivers of the health of populations. We have study after study showing that poverty, racial segregation, income inequality, and poor social cohesion are among the factors that matter most for population health. Public health is about ensuring the conditions for people to be healthy. To that end, these conditions should be central to the mission of public health scholarship, practice, and teaching.

You’ve said the recent outbreak of Ebola is a wake-up call concerning the importance of public health in an interconnected world. As dean, what can you do to keep sounding that alarm?

Schools of public health, as members of larger university communities, have three core functions: knowledge generation, knowledge transmission to our students, and knowledge translation to the broader community. This falls into the latter category. We have a responsibility to take our knowledge “off the shelf,” to use what we learn to inform and influence the public conversation. As dean, I’m committed to making sure SPH carries out that responsibility.

SPH is known for its boots-on-the-ground approach to public health: putting theories into practice. What’s your vision for how to move the school forward?

I am looking forward to engaging with the school community in strategic thinking throughout 2015 that helps us articulate the opportunities we have as a school to best realize our aspirations and act on our mission. Part of this will undoubtedly be identifying how we can capitalize on the school’s longstanding engagement with real-world public health. We are already doing much on this front, including reconceiving our professional MPH training to more fully embrace a role providing professional development and practical education opportunities for our students.

We will be looking to make sure that we provide ongoing education for our students—that our formal degree-granting programs, not-for-credit educational opportunities, and programs that engage students and alumni create a rich environment of lifelong experiential learning for all members of the SPH community.

On a lighter note: you’re moving your family from New York to Boston. Which way are you leaning, Yankees or Red Sox?

I grew up in Malta, moving to Canada just before college. So as a child, I grew up very much a football fan! I played the game everywhere—principally on the street in front of our house—and have loved the game ever since. I have been immensely lucky that my son also has grown up to love the game. So we are a soccer household. My son’s team is Chelsea, and mine is Juventus, but we both share a love of the New York Red Bulls. My son insists that our move to Boston will not shake his allegiance to the New York Red Bulls. I respect that! So I think we are going to remain New York soccer fans.

But in baseball, I confess to a fondness for the Red Sox. When I last lived in Boston, as a student in 1999, my wife and I lived in Fenway, just around the corner from Fenway Park. During that summer and fall, we could open our apartment window and hear the games being announced. We also went to games regularly and thoroughly enjoyed that.

So, I think we will indeed cast our baseball lot with the Red Sox—for old times’ sake.

Listen to Sandro Galea discuss his vision for the School of Public Health here. Video by BU Productions

Listen to Sandra Galea’s TED talk on the importance of context in an era of personalized medicine here.

Related Stories

SPH Dean Sandro Galea Appointed Robert A. Knox Professor

Leading expert on health consequences of mass trauma, conflict

SPH Dean Appointed to Minority Health Advisory Council

Sandro Galea will advise secretary of Health and Human Services

School of Public Health Has a New Dean

Sandro Galea: physician, epidemiologist, researcher, author

Post Your Comment