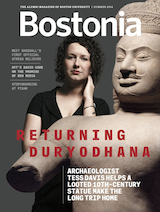

March 15, 1697, dawned cold and bright in Haverhill, Mass. Farmer Goodman Duston was riding his fields when he heard the shrieks of a raiding party of Abenaki, come to terrorize the small Puritan settlement. A few minutes later, Duston’s house was in flames, and his wife, Hannah, and week-old daughter, Martha, were gone, taken captive along with several neighbors. Martha was soon dead, her head dashed against a tree, and the Abenaki marched Hannah and the other captives northward into the wilderness.

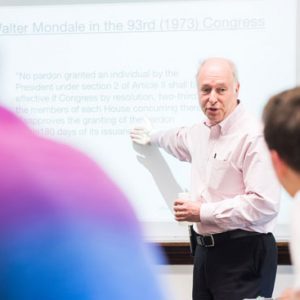

“It’s hard for us to imagine now, but Haverhill was the end of the world,” says Jay Atkinson, a College of Communication lecturer in journalism and author of a new book about her story.

Duston and two other captives—a woman and a boy—eventually found themselves in the custody of a smaller group of Abenaki, camped on an island at the junction of the Merrimack and Contoocook rivers in what is now central New Hampshire. The three carried out a bloody nighttime revenge, slaughtering their sleeping captors—two men, two women, and six children—with a poleax and hatchets. Then they navigated home down the icy Merrimack in a stolen canoe, ever fearful of encountering more hostile Native Americans.

Atkinson, a veteran journalist and author of seven previous books, grew up in Methuen, originally part of Haverhill, where a statue of Duston lauds her heroism. “I’d heard this story since I was a kid,” Atkinson says.

His Massacre on the Merrimack: Hannah Duston’s Captivity and Revenge in Colonial America (Lyons Press, 2015) alternates between thriller-paced accounts of Duston’s odyssey and measured examinations of the social, political, and religious landscape that brought the Abenaki to her door.

Duston’s fellow Puritans were astonished when she returned, a couple of weeks after her abduction, with the other two escapees and the scalps of their captors. She was invited to visit Rev. Cotton Mather, prominent businessman Samuel Sewall, and other luminaries of the day, and her husband successfully petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts for a reward. She received 50 pounds; the other escapees got 25 pounds each. While it’s difficult to provide an equivalent in today’s dollars, Atkinson notes that the Dustons used their money to buy additional land in the area, enough to provide farms for several of their children.

Atkinson began researching Duston’s story three years ago in libraries and museums around Haverhill and Methuen. “I’m within a few miles of one-of-a-kind materials,” he says. Duston artifacts he found in local libraries and museums include a hatchet and scrap of cloth purported to have been ripped from her loom by the Abenaki in the initial raid, as well as an account of her story written by Mather soon after her visit.

Atkinson has never been a stay-in-the-library kind of writer. Topics of his other books include his lifelong love of playing hockey (Ice Time) and rugby (Memoirs of a Rugby-Playing Man) and a year he spent working for a Somerville private detective (Legends of Winter Hill). So he set out to retrace Duston’s odyssey as closely as possible.

“I realized her story is as much a story of the landscape as it is of book study,” Atkinson says

Three years in a row on March 15, he visited the approximate location of the Duston homestead, now Haverhill conservation land. “It still looks a lot like it did in 1697,” he says. “Because of the tree cover, there was always snow on the ground where they would have taken her from her house and marched her along Little River. She would have been walking in snow.”

He rode his mountain bike, skied, or hiked over the approximate territory the settlers and their captors crossed as they moved north. Twice he canoed the icy Merrimack in New Hampshire to see the escape through Duston’s eyes.

The result is an account written with a novel’s vivid immediacy and detail, a pulse-quickening and sometimes gruesome account of the horrors Duston endured—and those she inflicted.

Atkinson doesn’t go easy on the leaders of the British Protestant settlers, and he’s even harder on the Quebec-based French Catholics led by Count Frontenac, who used native Americans as proxies in their struggle for hegemony over the New World in King William’s War.

“The fact that colonial authorities on both the English and French sides, including the government, military, and religious leaders, were a remarkably vain, conniving, greedy and thin-skinned lot, further complicated what was a thorny situation to begin with,” he writes.

Atkinson says he has heard from tribal leaders who dispute the accounts of brutality that Duston says she suffered and consider her a murderer unworthy of her heroic reputation.

“My thoughts about it continue to evolve,” Atkinson says. “When I first started, I thought she was totally justified, because they murdered her infant. I’m a parent. If somebody attacks my kid, I have to fight back.”

But he started thinking more and more about Duston’s story from the Indian point of view. “Is she a prototypical feminist? She’s unique as a female who fought back. But is she also a paradigm for the genocide that’s to come? Because she doesn’t kill just her oppressor, she kills the women and children,” he says.

“It was ugly, it was a bloodbath,” he says. “I started to feel more sympathy for the Abenaki.”

Related Stories

Learning What Makes Local Governments Tick, Here and Abroad

Initiative on Cities put three student fellows in public service this summer

The Devil Makes Them Do It

CAS prof on why Catholic exorcisms are spiking

BU Makes Way for Ducklings

Government & Community Affairs team helps rescue birds

Post Your Comment