In 2012, an estimated 43.1 million people in the United States were aged 65 or over, according to a 2014 US Census report. That number is expected to nearly double, to 83.7 million, by 2050. By 2030, more than 20 percent of US residents are projected to be age 65 and over, compared with 13 percent in 2010. This accelerating aging will present challenges to policy makers and programs such as Social Security and Medicare, as well as to families, businesses, and health care providers, the report noted.

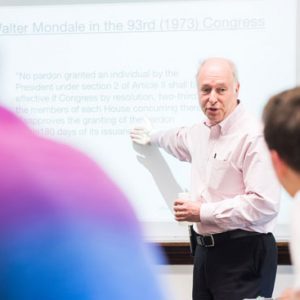

Ernest Gonzales, a School of Social Work assistant professor of human behavior and a Peter Paul Professor, argues in the Gerontologist, the journal of the Gerontological Society of America, that society needs to both recognize the valuable economic and social contributions of older people and provide more ways for older people to contribute through working, caregiving, and volunteering. Gonzales is a gerontologist and an expert on “productive aging,” as this kind of engagement is known. He and others in the field view productive aging as a benefit to society as well as to older people. But as Gonzales writes in his article, productive aging doesn’t come easily in our culture, hindered as it is by age discrimination, outdated social structures and policies, and health and economic disparities that make older people of color, as well as those of low income, more likely to suffer from obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other major illnesses and disabilities.

“The central questions are, how do we maximize productivity and be more inclusive of populations historically excluded,” Gonzales says. “We don’t want to force people to work longer or to be caregivers. But the reality is that working, caregiving, and volunteering can yield benefits to families and society. Engagement is naturally occurring, but as a rapidly aging society, how do we maximize it and expand opportunities and choices for engagement?”

Gonzales’ article, written with Christina Matz-Costa, a Boston College School of Social Work assistant professor, and Nancy Morrow-Howell, director of the Harvey A. Friedman Center for Aging at Washington University in St. Louis, appeared in a special March 2015 edition of the Gerontologist devoted to the 2015 White House Conference on Aging (WHCoA). Held once a decade since 1961, the conference is designed to help chart a national policy course on aging. The July 13 meeting focused on four major areas: retirement security, healthy aging, long-term services and supports, and protecting older Americans from financial exploitation and neglect.

In the months before the conference, the White House Conference on Aging website became a national forum for gerontologists, social workers, and experts like Gonzales. In February 2015, Gonzales organized colleagues at SSW and the School of Public Health into the WHCoA Working Group at BU. The group included SSW faculty members Sara Bachman, Thomas Byrne, and Melvin Delgado; Bronwyn Keefe, associate director of SSW’s Center for Aging & Disability Education & Research; and SPH professor Lisa Fredman. In addition to Gonzales’ article on productive aging, which grew out of his extensive research, the group produced a series of policy briefs on a range of topics, including caregiving, homelessness, and age discrimination in the workplace.

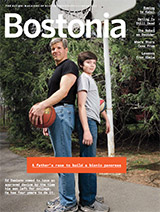

While no one was using the term “productive aging” at the time, Gonzales learned something about it as a boy growing up in a close, extended working-class family in Albuquerque, N.M., and El Paso, Tex., with grandparents who provided child care, spiritual guidance, and financial stability. “They were the cornerstone of the family in so many ways,” Gonzales says.

Because his parents were busy working—his father as a truck driver, his mother at a series of minimum-wage jobs—Gonzales spent every summer from age 5 to 14 with his maternal grandparents in El Paso. Eventually, he and his mother moved in permanently with his grandparents in El Paso. His grandfather, Guillermo Esparza, had a physically demanding but solid job as a construction worker for a concrete company and was the family’s primary breadwinner, Gonzales says. “I remember him coming home covered in cement,” he recalls.

After his grandfather retired in his early 60s, he not only took care of his wife, Felipa, who suffered from severe diabetes, he also cooked and cleaned for the entire family until shortly before his death, at age 77. “He spent 15 years taking care of my grandmother, of us, of himself,” Gonzales says. “He was the person in charge of the household.”

Gonzales’ Gerontologist article on productive aging generated considerable favorable response on the WHCoA website, including endorsement of his policy recommendations on age discrimination and Title V of the Older Americans Act from the Easter Seals, the National Urban League, Senior Service America, Inc., and Goodwill Industries International. Along with SSW graduate student Kate Goettge, he also contributed to a policy brief by Delgado that grew out of Delgado’s book Baby Boomers of Color: Implications for Social Work Policy and Practice (Columbia University Press, 2014). With Delgado as the lead author, the three describe the plight of “invisible” baby boomers of color. “Between 1999 and 2030, older adults of color age 65 and older will increase by 217 percent, compared to an increase of 81 percent for older white non-Latinos,” they write. And yet, “baby boomers of color are rarely discussed in the scholarly literature, lay press, or by policy makers.”

As a generation that has faced historic and persistent disparities in health care, Delgado and his coauthors write, “baby boomers of color are more likely to be uninsured and are at higher risk for obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hepatitis C, Alzheimer’s disease, and other illnesses and disabilities. They are also more likely to work in physically demanding jobs with a higher risk for workplace accidents and injuries, and they are more likely to be victims of violence.” These, and other factors—lower levels of English proficiency, undocumented status, barriers to access to high-quality health care—combine to put baby boomers of color “at greater risk for poor health and disability, reflecting the fact that race, racism, and health are inextricably intertwined.”

Retirement security is an especially important issue for boomers of color, who have historically earned significantly less than white workers, Delgado notes, and also have significantly less savings, and so depend to a far greater extent on Social Security. “For those who need or want to continue working,” he and his coauthors write, “the double jeopardy of race and age discrimination” may make it difficult to keep or find work.

At the same time, Delgado says, baby boomers of color should not be viewed primarily as “‘burdens’ with limited opportunity, ability, and resources to contribute in their old age.

“A new narrative, one focused on assets, is much needed,” he and his coauthors write. Many baby boomers of color have survived, and thrived, “in communities marked by violence, substance abuse, inferior schools, poor nutrition, and high rates of unemployment and imprisonment.” Their skills and experience “are particularly relevant to today’s marginalized communities.

“This is not a group to be overlooked,” they write. “Baby boomers of color are the first generation to come of age after the civil rights era, and this group has witnessed—and adapted to—profound changes over their lifetimes. Though there remains a significant gap between the health and socioeconomic status of boomers of color compared to their white non-Latino counterparts, boomers of color possess unique strengths, assets, and motivations to contribute to society.”

A version of this article originally appeared on BU Research.

Sara Rimer can be reached at srimer@bu.edu.

Related Stories

Framingham Heart Study Will Examine Aging with New $38M Funding

Seven-decades-and-running research project gets renewed funding for another six years

Trio of Young Faculty Earn Peter Paul Professorships

BU researchers study cancer, HIV, and an aging workforce

MED to Launch Physician Assistant Program

More than 1,000 apply for 28 slots in inaugural class

Post Your Comment