再保险

Th

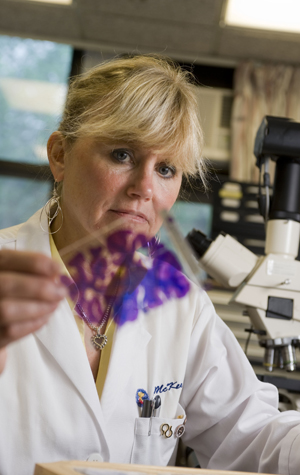

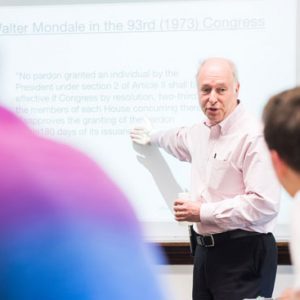

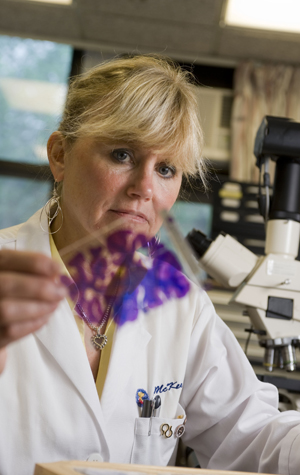

With the establishment of a national brain injury tissue bank, Ann McKee, a codirector of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, and her MED colleagues will be able to share their findings with scientists around the world. Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

Six years after McKee first identified CTE—at that time believed to occur almost exclusively in “punch-drunk” boxers—in the brain of a former NFL player, the condition still needs to be specifically defined, and clear criteria established to distinguish it from other degenerative brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s, McKee says. The brains of the former NFL players studied all showed severe damage in the frontal cortex, the part of the brain connected with insight, judgment, and intellect. That area was “completely congested and filled up with tau, an abnormal protein that forms tangles that strangle and destroy brain cells,” says McKee.

Diagnosed posthumously, CTE is an insidious degenerative disease with no known cure, so there is widespread and often false hope for experimental tests that might identify the disease in a living person. But before a reliable scan or other test is developed, “we need to validate the criteria” for the disease, says McKee. The new grant will drive this crucial first step. “We’ve been criticized in the past for being too insular,” she says. “Now we’re going to all the experts in the field, asking them to look at the tissue we’ve studied. Eventually there will be a web-based tissue site.”

Traumatic brain injury is a major public health problem and the leading cause of death in young adults, according to the NIH. McKee and her colleagues in the growing field of repetitive brain injury research are not only identifying the long-term brain damage caused by these injuries, they are striving to predict who, among football players and others at risk, is likely to recover and who will go on to suffer the degeneration known as CTE.

The grant provides “the long-awaited chance to fund our brain bank,” says McKee. “We’ve made tremendous progress; now we really need to spread out and study all different aspects of this disease, with researchers from all over the world—a wide net of researchers with different skill sets—addressing issues like genetic susceptibility and the nature of brain degeneration. The broader view is to apply what we know pathologically to clinical complications, to identify this disease in living people.”

As a member of the BU CSTE study because of the numerous concussions I suffered as the result of serious childhood accidents and my years playing high school and collegiate football, and due to the severe, repeated head trauma I suffered as a police officer in Los Angeles, California, I am very pleased with the news contained in this highly informative article.

Having worked with Dr. Robert Cantu and Dr. Robert Stern of the BU CSTE Program, after first speaking with Dr. Ann McKee, I have found the entire experience to be absolutely superb, from the introduction, through the preparation of my detailed medical history, and into the lengthy follow-up process.

Concussions are unseen, deadly, and I have learned just how insidious they can be and how long their effects can lay dormant. Throughout my journey with the BU team, (all of whom are to be commended, from support staff to doctors), I’m on an odyssey to find the most effective ways and means to combat the effects of traumatic encephalopathy.