Boston University graduate programs “Ban the Box” on applications to boost diversity, no longer requiring applicants to share convictions.

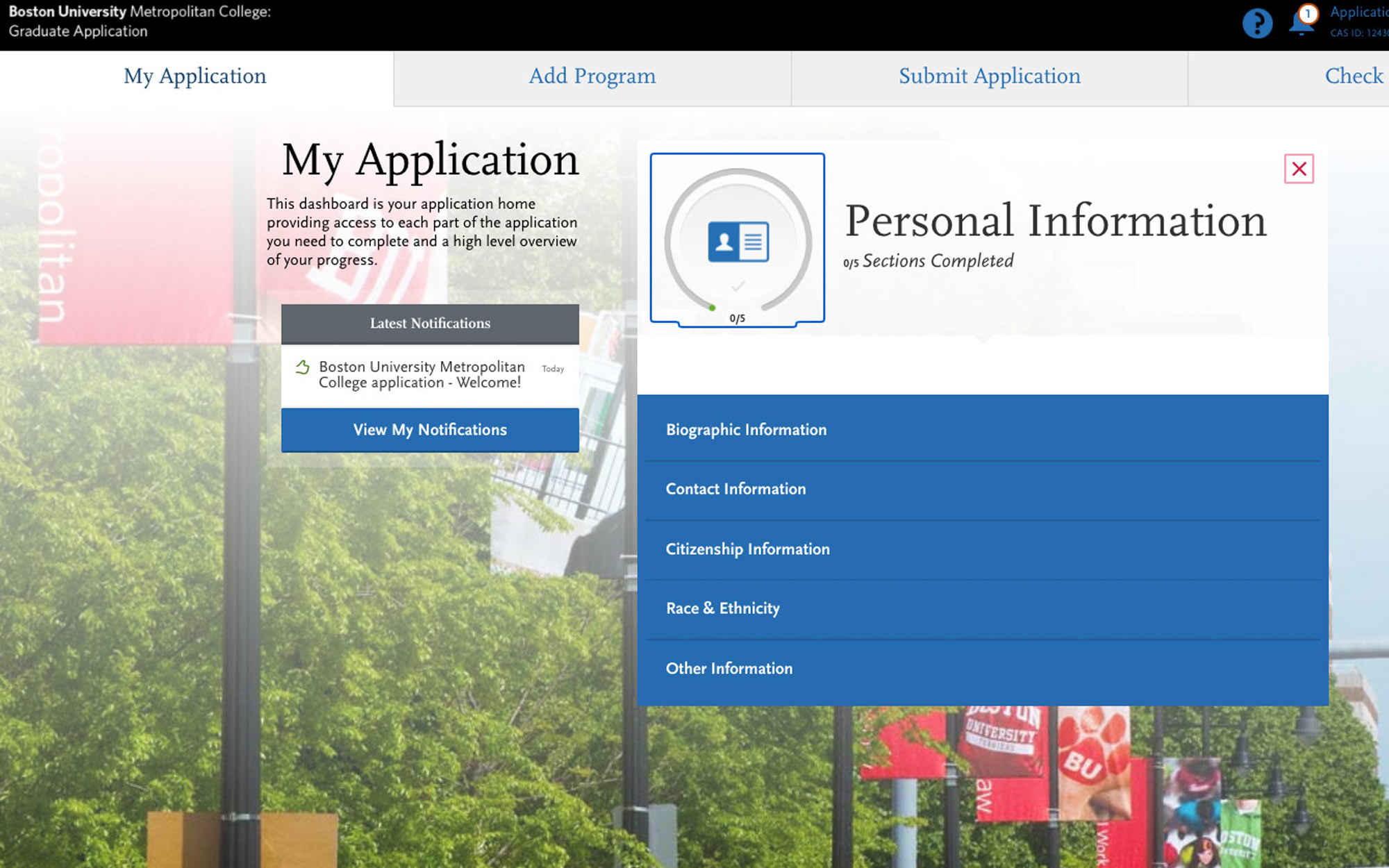

Applicants to BU’s Metropolitan College and more than a dozen other graduate programs will no longer be asked to disclose a criminal history on their application. Photo by Cydney Scott

BU Graduate Programs “Ban the Box” on Applications, Viewed as Contributing to Inequity

Applicants no longer have to disclose a criminal history, a change aimed at improving fairness in graduate admissions

Most graduate students applying to Boston University this fall will have a slightly different application than those who preceded them: a box that required applicants to say if they have a criminal conviction is gone.

Joining a movement called “Ban the Box,” the University has eliminated requiring the disclosure to encourage more diversity in admissions to its programs.

Daniel Kleinman, associate provost for graduate affairs and a College of Arts & Sciences professor of sociology, who shepherded the change, says race imbalances in the US criminal justice system mean that Black and brown applicants are overrepresented among applicants who must check the box, if they do at all. The box itself can be a deterrent to applicants of color who fear that by checking it they may be judged unfairly.

So it needed to go.

“It became clear to me that this was a matter of justice that we could act upon,” Kleinman says. By doing nothing, “we’re effectively harming our applicant pool, if not living up to our responsibility for diversifying our student population.”

It’s a proud moment for BU.

Momentum for the “Ban the Box” effort has increased exponentially in recent years, as support has grown for criminal justice system reforms, and more recently, for the Black Lives Matter movement. The Obama administration eliminated the box from a significant number of federal job positions in 2016, a move that delayed when an agency could inquire about an applicant’s criminal history until after a conditional job offer had been made.

Since then, 35 states and more than 150 cities and counties have adopted such rules in an effort to reduce the stigma of an arrest or conviction, according to the National Employment Law Project.

For spring, summer, and fall 2020, BU received 39,000 graduate student applications (not including the School of Law or the School of Medicine); 110 applicants acknowledged a criminal conviction.

Kleinman says the box was put on the applications as a safety measure, but the reality on the ground is different. Only 3.3 percent of college seniors who engaged in misconduct in college reported criminal behavior prior to attending college, he says, citing a 2013 study.

“There’s no evidence having this box makes universities safer,” he says.

During the past academic year, BU’s Prior Conviction Review Team, a panel that reviews applicants and includes members from the Office of the Provost and the Office of the General Counsel, considered about 10 cases of the 110 who acknowledged a conviction (not all of whom were accepted). Without the check-the-box requirement, Kleinman says, the team will disband.

The effort to remove the box was slow and complicated, he says, at a University that is home to 17 graduate schools, each with its own application.

A year ago, a former associate dean approached Kleinman with research literature on the change, prompting him to dig into the issue. When he was convinced, he sought and won the support of administrators, the Graduate Council, and BU’s Council of Deans, who also wanted to review current research.

Jessica Simes, a CAS assistant professor of sociology, lobbied administrators to make the change, calling it “an important step for BU in building a just institution.”

A recent national audit study examined the effect of criminal record questions on college admissions and found the rejection rate for applicants with felony convictions was nearly 2.5 times the rate of those without convictions; Black applicants with criminal records were particularly penalized when disclosing a felony record, Simes says.

“It’s a proud moment for BU,” says Simes, coauthor of a forthcoming book about the community-level impacts of mass incarceration and the US prison boom. She says it expands opportunity by reducing bias in the graduate school admissions process.

“It opens the process to those who may not have applied fearing discrimination,” she says, “and sends a message that BU stands for fair and just admissions processes.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.