Robin Williams Revealed, with Big Help from BU Archives

New York Times author’s new book uncovers surprising truth about late comedian’s famous spontaneous riffs

Comedian and Academy Award–winning actor Robin Williams was so wildly inventive and spontaneous that he made up all his riffs and routines on the fly. Or at least, that was the legend of the brilliant but troubled Williams, who was 63 when he died from suicide in 2014.

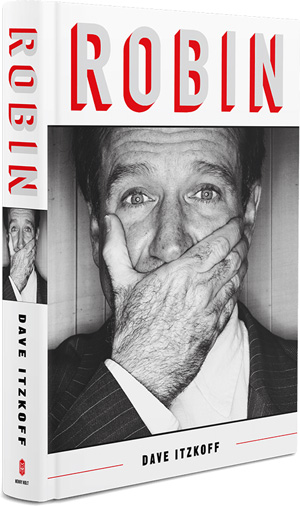

Except, as New York Times culture reporter Dave Itzkoff writes in his acclaimed 500-plus-page New York Times best-selling biography Robin (Henry Holt and Company, 2018), the legend was more fiction than fact. Itzkoff, who will talk about his book Tuesday night at the Metcalf Ballroom, uncovered Williams’ more complex creative process through exhaustive research, including more than 100 interviews with family and friends and the directors, writers, actors, agents, and comedians the actor worked with.

Also central to his understanding of that creative process, says Itzkoff, were Williams’ papers, which he donated to BU’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center in 2011, after Gotlieb director Vita Paladino (MET’79, SSW’93) had begun a correspondence with him about them. Among other materials, Itzkoff poured through countless handwritten notes Williams had made for jokes and comic performances as well as for scenes in movies and television shows.

“He was a very talented ad-libber and improviser, and he did make up a lot of the stuff on the spot in performance,” says Itzkoff, the author of three previous books, Mad as Hell (about Paddy Chayefsky and the making of the iconic 1976 film Network), Cocaine’s Son, and Lads: A Memoir of Manhood. “But what you see through the papers is how much preparation went into looking as off-the-cuff as he was. There was a lot of research and a lot of note-taking, and dry runs that he went through and a lot of organization and practice.”

Itzkoff makes it clear in his book that he was a fan of Williams, chronicling the performer’s spectacular successes, his devotion to friends like Billy Crystal, Christopher Reeve, and Richard Pryor, and his love of his family. But he doesn’t shy away from the messiness—the three marriages, the struggles with addiction, the deep insecurity.

“The real Robin was a modest, almost inconspicuous man, who never fully believed he was worthy of the monumental fame, adulation, and accomplishments he would achieve,” writes Itzkoff, who had interviewed the actor extensively between 2009 and 2013 for New York Times articles.

BU Today talked with Itzkoff about his research for Robin, how he organized his writing time—he credits, in part, his then-new baby—and about the similarities between his own father, who is in long-term recovery from a cocaine addiction, and Williams, who had also suffered from addiction and was sober at the end of his life (Itzkoff writes in his book that Williams’ death was complicated by Parkinson’s disease and undiagnosed Lewy body dementia).

BU Today: In your memoir, Cocaine’s Son, you write about your father’s addiction while you were growing up. Did you empathize with Williams’ son Zak, who had to cope with his father’s addictions, and with Williams himself?

Oh, sure. I think it’s very relevant, even though they’re different people and had different experiences, I certainly think there are some commonalities. Both my father and Robin were recovering addicts, and there is a kind of a similar personality in that they were both extremely—because of their drug experiences, their recovery experiences—confessional people, as recovered addicts sometimes are. They want to tell you all these things about their lives. They want to tell you about the people they used to be when they were still getting high, the regret and remorse they feel, and how they’re different people now and you don’t have to scratch them very deeply to get these kinds of stories, that kind of information out of them. They really aren’t abashed or reluctant about it.

Your acknowledgments say the Gotlieb Center archives—Williams’ papers—at BU were “an invaluable resource.” And you have many footnotes referring to the material: scripts, notes, letters, things like that.

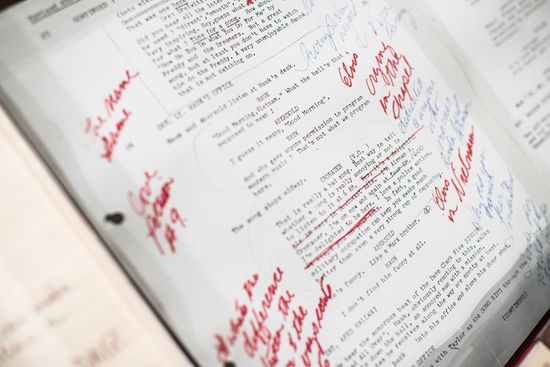

The University should be extremely proud of it. It was such a one-of-a-kind resource, and just absolutely essential to my work. In some ways, Robin’s process is kind of locked away from us. A lot of it is internal and in his head. He wasn’t particularly good all the time at setting it down on paper, but because we have not only the annotations he made himself on his various scripts…but also the notes he and other people kept on his stand-up routines and performances—that’s pretty massive in terms of a piece of the puzzle.

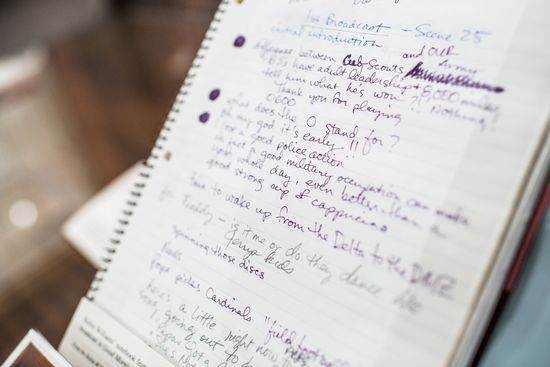

It’s a huge piece to have because I think there is this assumption that everything that he did essentially he made up off the top of his head…. There was a lot of research and a lot of note-taking, and dry runs that he went through and a lot of organization and practice.

What are some of the things from the archives that were a big help?

A lot of the stuff about Good Morning, Vietnam [in that 1987 movie, Williams plays a disc jockey who hosted an Armed Forces Radio program in Saigon in the mid-1960s] and how he created the Adrian Cronauer disc jockey. I talked to director Barry Levinson and other people who worked on the film, but in terms of seeing Robin’s own process, that came right out of his papers.

In the archives you see the research materials that he took with him to Thailand when they were filming—all this information about the mid-1960s Vietnam War–era history that a disc jockey would have known and been talking about. You see the notebooks that he and Marsha [Williams’ second wife] kept. He would basically shoot by day and go home at night and improvise—play around with the facts he was reading up on, coming up with little bits. Either he or she would write them down in notebooks or on paper and they would try to organize them…and maybe he would have 20 different jokes…and [decide] how do I put them in an order that would sound like a spontaneous routine? Even then he’s making these things up; he’d go in front of the camera with 20 different bits in his back pocket, deciding in real time what order to put them in, tweaking them.

Did the folks at the Gotlieb Center just start bringing the boxes to you?

I was there for a week. I just had them bring every box of physical material. There were some digital recordings I didn’t have time to go over, but everything else that was physical—every piece of paper or photograph—I asked to see. I spent a week going through all of it and taking tons of notes and not even thinking about what is in it: don’t try to think about what’s significant about it or try to piece together a narrative in your head at this stage—just take notes, think about how cool this is and how amazing…. Seriously, there were business cards that he printed for himself from the first improv team in Los Angeles—this group called Off the Wall.

It’s sort of amazing that he saved all that stuff…

Yeah, it’s pretty extraordinary, right? He wasn’t always the most organized person…. It was sometimes hard for him to admit or to really articulate or to say out loud, but on some level he was also someone who thought he was possibly destined for a great career, had the potential for it. We all want to save things that are important to us and hope that one day when they’re pieced together and laid out, they will tell the story of who we were.

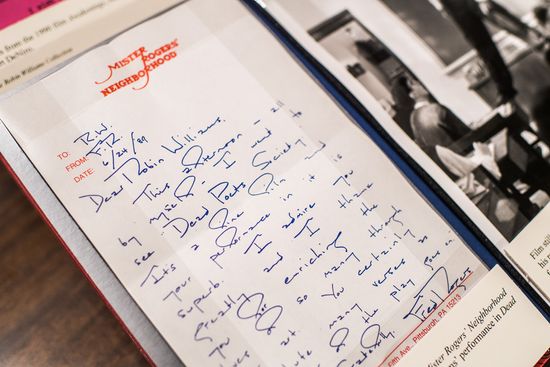

You cite a lot of letters he wrote, many in the Gotlieb archives. That was an era when people were still writing letters…

There were also a lot of letters to him, which is fascinating. There’s a letter Mr. Rogers [Fred Rogers, the creator of the children’s television show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood] wrote to him after he saw Dead Poets Society, which blew my mind. If you think about potentially any movie in Robin Williams’ film résumé that would potentially resonate with Mr. Rogers, that’s probably the best one. In some ways their worlds and lives could not be more different. One was a children’s entertainer. One was aimed more for adult audiences. The kind of stuff Robin was known for in that era was very often vulgar and profane and not necessarily Fred Rogers’ cup of tea.

That was one of the things I found most moving about your book—the network of close friendships Robin Williams had.

In some ways, there are a lot of lessons in his story, but one lesson is that he is just a person. The celebrity aspect of it was so hard for him, and it prevented him at times from just having the kind of normal human existence that he wanted. And he still had all these kinds of failings and misfortunes that occur to all kinds of people, and he dealt with them, no differently than any other kind of person would, regardless of his stature or his wealth at times. Having these close friendships…was tremendously important to him. He was a social person. He needed that interaction, that reinforcement.

This was a massively researched book—did you actually write it and work full-time at the New York Times at the same time you and your wife had just had your first child?

Yes, I did.

How?

It’s a weird thing and people don’t believe me, but I think having a child early in the process of this was extremely helpful—not that everybody can do it, not that I’d say, ‘Hey, if you’re going to write a book, make sure your wife has a child in the first year of it.’… The experience really forces you to think about how you use your time—what free time you have outside of your parenting. On a given day, when you know you’re going to have, let’s say, a window of two or three hours, you better take advantage of it, because if you don’t, you might not get another window, and it’s lost to you.

Do you have any advice for students who want to be writers—who want to be journalists?

If that’s something they’re interested in, they should absolutely pursue it. There’s no disguising what’s happening to media right now—the kinds of traditional and more monolithic journalism outlets like the Times are few and far between. And there are fewer regional newspapers, even the weekly magazines that I cut my teeth at, that’s all pretty much gone or going away. They’re being replaced by other kinds of outlets and platforms that were barely in their infancy when I got out of college. I would have loved to have taken advantage of that when I was young, just to be able to write and publish for myself. I probably would have published some things that I’m glad are not retrievable now, that can’t be found by Google search.

By and large, I think that’s good for writers starting out, if nothing else, just to write for themselves, and to be able to share it with others, and hopefully as a way to refine your own interests and find out what you’re curious about. Just having the experience of having an audience respond to what you write, seeing what that’s like, and being part of a conversation around something—I think that’s invaluable.

Dave Itzkoff will speak at the George Sherman Union Metcalf Ballroom, 775 Commonwealth Ave., Tuesday, April 30, at 6 pm. The event is sponsored by the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, part of the Friends Speaker Series. An exhibition of the Robin Williams archives will be on display.

Admission to the event is free to students with a BU ID and Friends of HGARC, and $25 for members of the public.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.