Public Health and Baltimore

How the death of Freddie Gray stirs conversation about the impact of racism on individual health

In 2014 and 2015, the list of incidents in which police have been involved in harming unarmed black men seems inexhaustible. Earlier incidents involving Amadou Diallo and Sean Bell have been followed, since August 2014, by Michael Brown, Walter Scott, Eric Garner, and, in April 2015, Freddie Gray.

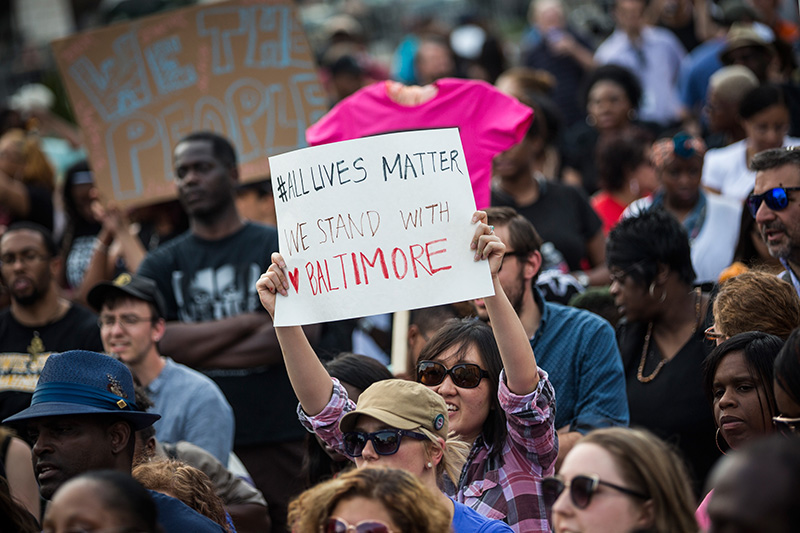

These events have been accompanied by an outpouring of anguished civic protest, and by commentary that has noted how racism in US life continues to loom large and shape our experiences and interactions. But the events do not capture the extent of racist social interactions and structures that shape the experiences of millions beyond those whose plight reaches the news. And the barrage of daily headlines largely obscures the significant public health consequences of racism, both interpersonal and institutional.

For those of us in an academic setting, charged with generating research and translating our findings to both students and the public, the recent events stir us to recommit to better understanding the health consequences of racism and conveying their import to the broader community. Racism and hate of any kind are intolerable, separate and apart from their health consequences. But health, as a universal aspiration, can serve as a clarifying lens for action—as one more tool to elevate these issues in a national conversation that will continue long after calm has returned to the streets of Baltimore.

Th

In terms of structural racism, research has disclosed institutional barriers to fair and equitable treatment, and that this treatment is associated with poorer health. Much of the work on structural or institutional discrimination has centered on residential segregation and unequal access to health care. For example, a geographically weighted approach demonstrated that residential segregation was associated with black-white differences in congenital heart disease mortality. And a more recent analysis demonstrated a beneficial effect of the end of Jim Crow laws (i.e., legal discrimination) on the reduction of premature mortality for blacks, accounting for age, income, and other effects, while a related analysis demonstrated a similarly beneficial effect on the black infant mortality rate. Critically, however, there is a striking dearth of research on institutional and structural racism, relative to the now-large body of work on interpersonal racism.

As members of an academic school of public health community, we have a special obligation to engage in the issue of racism. Events like those unfolding in Baltimore urge us to recommit to a scholarship of consequence that shines a light on the root causes of the racial divides that underlie the daily headlines and the links between racism and public health. This, of course, suggests prioritizing our research questions, focusing on what matters most, and orienting our scholarship toward areas of inquiry that tackle the foundational drivers of population health.

In our roles as teachers, recent events call for an education that is dynamic and reflexive, but also an educational environment that encourages and respects sharing of ideas toward the goal of identifying solutions grounded in diversity of experience, opinion, and perspective. It is simply not enough to accept that our educational program is rooted in concern around issues of disparities; we need to engage in hard, sometimes uncomfortable, discussions about these issues.

Because public health rests on the generation of conditions that make people healthy, we need to work toward a health conversation that extends well beyond our academic walls. It is our task to inspire a dialogue that explores and explains the links between our interactions and our health—and how these links may be broken.

Galea is dean of BU’s School of Public Health and an expert in urban health, trauma, and social factors in health outcomes.