Boston Rocks: For 40 Years, BU Has Been Turning Up the Volume

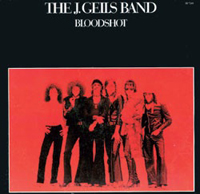

Boston has a long history in rock and roll, and the music scene often swirled around Boston University. As the psychedelic era waned in the late ’60s, the city entered a serious rhythm-and-blues boom, kicked off largely by its first superstar band, the J. Geils Blues Band. They started out as a reverent group of blues scholars and record collectors and slipped into high gear when they moved to Boston from Worcester, dropped “Blues” from their name, and brought in former art student, sometime WBCN DJ, and full-time wild man Peter Wolf as lead singer. The band honed its skills through weekly gigs at the Catacombs, a basement club on Boylston Street.

There they met Seth Justman (CGS’71), a keyboardist who became the last member of the original group. Five years younger than the others, he worked hard to get accepted. “We gave him an audition, and he shows up schlepping this big organ,” guitarist Geils recalls. “Wolf was immediately suspicious. ‘What’s that, a piece of your grandmother’s furniture?’ But once we heard him play it was, ‘Yeah, man!’” It proved a smart decision — Justman wound up writing, with Wolf, the band’s two greatest hits, “Centerfold” and “Freeze Frame.”

Hot on the heels of the J. Geils Band came a pair of blues-drenched party bands, Duke and the Drivers and the James Montgomery Band, which ruled both colleges and clubs in the early ’70s. If you liked sweaty grooves and wanted a perfect soundtrack to a night of alcoholic libation, these were likely your favorite bands. Indeed, when the Drivers — which included keyboardist Tom Swift (CGS,’71, CAS’73) and singer and sax player Andrew Hixon (CAS’72) — played Paul’s Mall on Boylston Street in 1974, the club is said to have set an all-time record for beer sales.

It says something about Boston’s reputation at the time that James Montgomery (DGE’69, CAS’71) moved here from Detroit, no slouch of a music city itself. “I chose BU because of the music scene,” he says. “In Detroit you could see two or three great bands a month. Here you could see that every week.” With his wailing harmonica, lean and hungry look, and flashy clothes, Montgomery became a local fixture, a favorite jamming partner of Bonnie Raitt’s and an occasional drinking buddy of Mick Jagger’s, who dropped in “with two blondes and a limousine” for a memorable New Year’s Eve gig with Montgomery in New York in 1982. Montgomery is still a mainstay of the Boston blues circuit; in recent years he’s been leading his own band as well as playing harmonica with guitar hero Johnny Winter.

Punk renaissance

In the mid-’70s, something happened in Kenmore Square. Jim Harold, owner of the Rathskeller — affectionately known as the Rat — bucked the local pattern by booking bands that played their own material. Odds are that Harold didn’t have any grand designs in mind; he simply couldn’t afford the polished disco cover bands that played across the street at Narcissus. But it was enough to give the new phenomenon known as punk rock an unofficial home.

With its fallout-shelter ambiance and mysteriously sticky carpets, the Rat looked as gritty as the music sounded. Each night you could catch now-legendary Boston bands like the Neighborhoods, the Real Kids, Willie Alexander, and even the Cars and the Pixies before they became famous (the Pixies got their record label deal, with the British label 4AD, after a Rat showcase).

Before long the scruffy, low-budget scene had leaked out to clubs all over town — at Cantone’s downtown, at the Channel near South Station, and at Bunratty’s in Allston. But Kenmore after dark remained its heart: a sea of black leather that migrated from the Rat to the late-night food spots like Deli Haus and the Pizza Pad. For a while there was a second club, Storyville, just across the square, where Pizzeria Uno now stands. Instead of competing, the two clubs agreed to stagger their sets so listeners could cross the street and catch both headliners.

One of the great Rat-era bands had its roots in Warren Towers. Even before he enrolled at BU in 1975, Connecticut native Jeff Conolly had a reputation as a music nut; in high school his fanatical record-collecting had earned him the nickname Monoman. Conolly learned that his Warren downstairs neighbor Adam Schwartz (CGS’77), who went by the name Adam Bomb, was singing in a band called DMZ, and he wangled an invitation to a rehearsal. Schwartz argued with the band that night and stomped out. Instead of trying to smooth things out, Conolly turned to the band and asked if they knew any Iggy Pop songs. By the end of the night Schwartz was out and Monoman was in.

Conolly’s rock career lasted longer than his tenure at the University. The BU dropout’s second group, the Lyres, founded in 1979, is still going strong. The sight of Conolly shaking his blond hair and banging a tambourine became familiar in town, and he’s well known to lovers of raw and raucous garage rock.

In later years BU would leave a mark on music from hard-core punk (three-quarters of the band Sam Black Church) to abstract pop. Indeed, some of the best alternative rock in the ’80s and ’90s came from female songwriters with a maverick streak. High on the list were two friends who met at Freshman Orientation, Mary Timony (CAS’92) and Joan Wasser (CFA’93). They went on to two of the era’s more original bands. Singer and multi-instrumentalist Timony led Helium, which blended punk aggression with classical touches, fairy-tale imagery, and sexual politics. Despite her demure look offstage, Timony, with her intense stare, cut a no-nonsense figure onstage.

Wasser became that rock and roll rarity: a lead violin player, whose guitar-like sounds and visual flamboyance made a strong impression with her band, the Dambuilders. The two women’s paths often crossed, and Wasser even joined Helium for a time. Both are now solo artists. A recent set at the South by Southwest new music conference in Austin earned a Rolling Stone magazine rave for Wasser’s latest project, Joan As Police Woman.

Some aficionados of the BU rock world would say the party ended when the Rat shut down in 1997. Certainly one needs to look hard to find any trace of rock and roll in the newly gentrified Kenmore Square. But some people do look hard.

“I think the spirit is always here,” says Jordan Harrison, who is the Web communications manager for the BU School of Public Health when she’s not singing for one of the current club scene’s most popular bands, World’s Greatest Sinners. “If anything, there are more bands now, but it’s more diversified, so you don’t feel it in that intense Kenmore Square way.”

The Paradise remains, more upscale than it was two decades ago, and to hear the next big rock stars before they make it big, these days it’s necessary to venture into Allston or Cambridge. Still, if it’s true that, as they say, rock and roll will never die, somebody’s going to dig up a dusty old J. Geils Band album, find a cheap guitar, and write the next chapter in the long story of BU rock.

Brett Milano (COM’82) is the author of The Sound of Our Town, published this month by Commonwealth Editions.