A Conductor on the American Classics: CFA at Symphony Hall

Part one: Charles Ives and the break with the European tradition

On Monday, December 3, the Boston University Symphony Orchestra andSymphonic Chorus will perform the first of two annual concerts atBoston’s Symphony Hall. More than 250 musicians — mostly from theCollege of Fine Arts school of music, but representing other BU schoolsand colleges as well — rehearse for weeks preparing for theperformance, which Ann Howard Jones, a CFA professor of music anddirector of choral activities, describes as an “experience that can seta standard by which all of their music-making can be measured.”

“Thegoals for the performance are to reach artistic heights that areenhanced by playing and singing in a hall where the musicians canreally hear themselves,” she says. “A young performer’s musicaleducation is not complete without excellent performance of music of thehighest possible quality.”

Monday’s concert features works by American composers, including Charles Ives’ Psalm 90, Samuel Barber’s Prayers of Kierkegaard,and Aaron Copland’s Third Symphony. David Hoose, a CFA professor ofmusic and director of orchestral activities, who will conduct theorchestra, shares his thoughts on the works with BU Today.Below, Hoose reflects on Ives’ role in furthering the Americanclassical tradition in the early 20th century. Check back on Friday forhis exploration of Barber’s iconoclastic style and religious themes,and on Monday for his thoughts on Copland’s World War II–era reflectionon America.

Monday’s performance takes place at 8 p.m. atSymphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Ave., Boston. Tickets are $35, $20,and $10 and are available at the Symphony Hall box office,617-266-1200, and the Tsai Performance Center box office, 617-353-8724.For more information, click here.

Charles Ives’ Psalm 90

By David Hoose

IfAmerican classical music ever had a characteristic and identifiablelanguage, before ubiquitous communication began to flatten nationaldistinctions, it was Charles Ives who pioneered its growth spurt,Samuel Barber who helped nurture its heart, and Aaron Copland whoreveled in its full flower. Before Ives, there were many fine Americancomposers — Edward MacDowell, John Knowles Paine, Amy Beach, HoratioParker, Charles Griffes. But even though they all had distinctpersonalities, they were essentially European voices. None (saveperhaps, the oldest of all, William Billings) severed deep ties with amulticentury, powerful, magnificent, and still-thriving musicaltradition. None attempted a breakthrough to a frontier in the spirit ofthe Wild West, the waging of a civil war to abolish slavery, or eventhe building of the transcontinental railroad.

But Charles Ivesdid, and he thoroughly succeeded in changing — or ignoring — thevenerable musical rules. Although he grudgingly tried to followEuropean models in his earliest music — everyone, even the mosticonoclastic mind, must start with fundamental principles before he caneffectively break them — Ives didn’t find the tried-and-trueconventions useful, and soon he tore away from them. Even as a child,he had fooled around with cacophonic sounds that would have scaredanyone. And so, experiments with intricate and complex rhythms, layerupon layer of seemingly unrelated musics, and wildly dense harmoniesbecame as possible and probable as any simpler utterance, and theparticular logical thought that had guided Western music for 300 yearsbegan to lose its grip. Charles Ives, more than any American composer(and perhaps more than any European composer except Monteverdi)delighted in the revolution of turning evolution on its head.

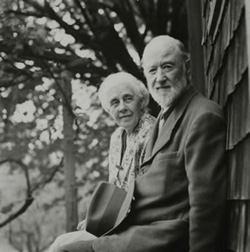

Among Ives’ more than 40 compositions for chorus, his 1923 setting of Psalm 90,for chorus, organ, three sets of bells, and low-pitched gong, standstallest. The setting was his attempt to reconstruct a lost work fromabout 30 years earlier, but this transcendent second version probablybears little resemblance to the original. In this later one, Ivesbeautifully integrated innovative choral writing and the naturalutterance of church anthems to capture perfectly the design, drama,breadth, and fervency of the psalm. Recognizing what he had achieved,Ives — an inveterate tinkerer — left this Psalm 90 untouched, telling his devoted wife and companion, Harmony, that he thought it his most perfect creation.

It is undoubtedly one of his most powerful creations. And while not the craziest piece Ives ever wrote, Psalm 90is nonetheless one of his most visionary. The firmament — or God’sinfinity — is present in an unvarying low C played by the organ pedal,from the first to the last measure. Before the chorus enters, the organsuspends above the immovable foundation a succession of harmonies, eachgiven its own signature: the Eternities — Creation — God’s wrathagainst sin — Prayer and Humility — Rejoicing in Beauty and Work.Neither sung nor spoken, but simply imagined, these words and theirassociated harmonies presage the entire journey ahead. Although Ivesnever embraced a Christianity of exclusivity (“The soul is each man’sshare of God,” he wrote), this predetermination of what is to comesuggests his roots in Calvinist predestination. Distant bells, theheavenly bells that will sound again only at the end, fleetingly appearover the final introductory chords; as they fade, the chorus begins.

Ea

Inthe final peace-filled verses, the bells, both of the white-steepledchurch and of heaven’s freedom, surround the congregation in acomforting haze.

Charles Ives composed no significant music after completing his Psalm 90.One day in 1926, he came down from his study and, with tears on hisface, said to Harmony, “I can’t seem to compose any more. I try and tryand nothing comes out right.” For 30 more years, he scribbled, revisedold works, fussed at himself and the world, and grew depressed, untilhe died in 1954.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.